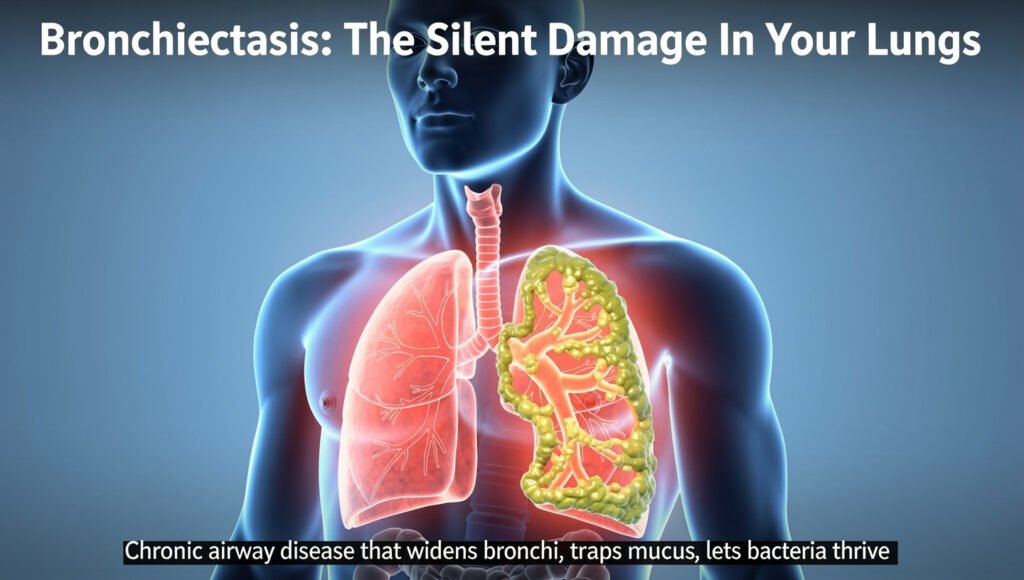

Bronchiectasis may be silently affecting your lungs right now without you even knowing it. This chronic airway disease causes permanent widening of your bronchial tubes, creating pockets where mucus accumulates and bacteria thrive. Unlike asthma or COPD, bronchiectasis often goes undiagnosed for years, with prevalence rising 8% annually in the United States alone. Your airways’ natural cleaning system breaks down, trapping secretions that trigger persistent coughing, recurring infections, and progressive lung damage. Understanding this condition is crucial because early diagnosis and proper management can significantly slow disease progression and improve your quality of life. As the third most common chronic airway condition, bronchiectasis deserves your attention and awareness.

Key Takeaways:

- Bronchiectasis is far more common than previously thought. With a global prevalence of 680 per 100,000 people and U.S. cases rising 8% annually since 2001, this condition now ranks as the third most common chronic airway disease after COPD and asthma. Between 350,000 and 500,000 Americans have bronchiectasis, though the actual numbers are likely higher due to frequent misdiagnosis.

- The disease operates through a self-perpetuating “vicious vortex.” Four interconnected components-chronic bacterial infection, sustained inflammation, impaired mucus clearance, and irreversible structural lung damage-continuously reinforce each other. This creates multiple feedback loops that accelerate disease progression, making early intervention vital.

- Permanent airway damage disrupts the lungs’ natural cleaning system. When airways become widened and distorted, the microscopic hair-like cilia can no longer effectively sweep mucus out of the lungs. This allows bacteria to colonise pooled secretions, triggering inflammation that further damages tissues and creating an environment where infections thrive.

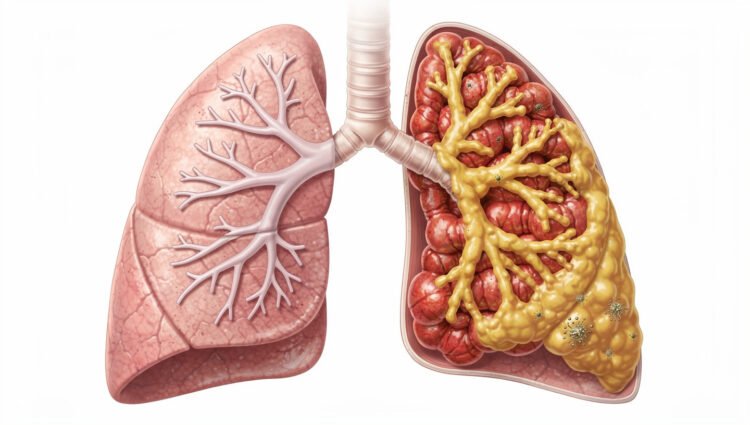

- Structural damage varies in severity and appearance. CT scans reveal three distinct patterns: cylindrical (uniform widening), varicose (irregular beading), and cystic (severe balloon-like sacs). The cystic form represents the most extensive destruction, while many patients display mixed patterns across different lung areas.

- Disease-modifying treatments are emerging for the first time. After 200 years of documented history, bronchiectasis is finally receiving attention from researchers and pharmaceutical developers. Multi-pronged treatment approaches that target different components of the vicious vortex show the most promise for slowing disease progression.

Understanding Bronchiectasis

Structural airway damage doesn’t happen overnight. The transformation from healthy bronchi to permanently dilated, dysfunctional airways typically unfolds over months or years, often triggered by an initial insult that sets the destructive process in motion. This insult might be a severe respiratory infection during childhood, repeated bacterial pneumonias, an immune system deficiency, or exposure to toxic substances. In approximately 40-50% of cases, however, no identifiable trigger can be found-a classification physicians term “idiopathic bronchiectasis.” What unites all cases is the result: airways that have lost their structural integrity and can no longer perform their necessary function of efficiently moving air and clearing secretions.

The consequences extend far beyond simple airway widening. As bronchiectasis progresses, you may experience a daily productive cough, recurrent respiratory infections, progressive breathlessness, and fatigue that interferes with everyday activities. The pooled mucus becomes an ideal breeding ground for opportunistic bacteria, leading to exacerbation periods of worsening symptoms that require antibiotics and sometimes hospitalisation. Each exacerbation potentially causes additional airway damage, accelerating the disease trajectory. Quality-of-life studies consistently show that bronchiectasis impacts physical, emotional, and social well-being to a similar extent as other chronic respiratory diseases. Yet, it receives considerably less research funding and public awareness.

Definition and Pathophysiology

Medical textbooks define bronchiectasis as abnormal, permanent dilation of the bronchi caused by destruction of the elastic and muscular components of the bronchial wall. This clinical definition, while accurate, doesn’t fully capture the complexity of events at the cellular and molecular levels. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scanning, the gold standard for diagnosis, reveals bronchi that measure larger than their accompanying blood vessels, a reversal of the normal anatomical relationship. You might see airways that don’t taper as they branch toward the lung periphery, or bronchi that remain visible in the outer third of the lungs where they should become too small to detect. These radiological signs translate into tangible functional impairments that affect daily life.

The pathophysiology involves a cascade of destructive processes. Neutrophil elastase, an enzyme released by inflammatory cells, breaks down elastin and collagen in airway walls, while bacterial toxins and inflammatory mediators further compromise structural integrity. Studies measuring airway inflammation in patients with bronchiectasis have documented neutrophil counts 100 to 1,000 times higher than usual, along with elevated levels of interleukin-8, tumour necrosis factor-alpha, and other pro-inflammatory cytokines. This inflammatory soup doesn’t just damage airways; it also impairs the function of remaining cilia, alters mucus viscosity through changes in mucin composition, and creates an oxidative stress environment that perpetuates tissue injury. Research using bronchoscopy samples has shown that, even in stable disease, significant inflammation persists, explaining why symptoms rarely disappear completely despite treatment.

Classification of Bronchiectasis

Clinicians classify bronchiectasis along several dimensions, each providing insights into disease severity, prognosis, and treatment approaches. The most fundamental distinction is between cystic fibrosis (CF) bronchiectasis and non-CF bronchiectasis, as CF is a specific genetic condition with distinct management protocols. Within non-CF bronchiectasis, classification by aetiology attempts to identify the underlying cause: post-infectious (following severe pneumonia, tuberculosis, or childhood whooping cough), immunodeficiency-related (primary antibody deficiencies, HIV), allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), connective tissue disease-associated (rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s syndrome), or related to airway obstruction, aspiration, or ciliary dysfunction disorders like primary ciliary dyskinesia.

Severity classification systems help predict outcomes and guide treatment intensity. The Bronchiectasis Severity Index (BSI) and FACED score are validated tools that incorporate factors including age, body mass index, lung function measurements, extent of radiological disease, bacterial colonisation status, and exacerbation frequency. A

Morphological Types of Bronchiectasis

Understanding the structural patterns of airway damage in your lungs provides essential information about your disease severity and prognosis. When radiologists examine your high-resolution CT scan, they classify bronchiectasis into three distinct morphological types, each representing a different degree of bronchial wall destruction and dilation. These classifications aren’t merely academic-the type of bronchiectasis you have correlates with symptom severity, bacterial colonisation patterns, and your response to treatment. Studies have shown that patients with more severe morphological types experience more frequent exacerbations, with some research indicating that those with cystic patterns have nearly twice as many hospitalisations compared to those with cylindrical disease.

The morphological classification system has evolved significantly since bronchiectasis was first described in the 1800s. Before the advent of CT imaging in the 1980s, physicians relied on bronchography, a now-obsolete procedure that involved injecting contrast material directly into the airways, to visualise bronchiectasis. Today’s high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) provides exquisitely detailed images of your airways without invasive procedures, allowing radiologists to identify bronchiectasis as mild as 2-3mm in diameter. Your specific morphological type reflects the cumulative damage your airways have sustained, whether from repeated infections, inflammatory conditions, or underlying genetic factors. Perceiving the morphological pattern in your lungs helps your healthcare team tailor treatment strategies to address your specific disease characteristics.

- Cylindrical bronchiectasis shows uniform airway widening with parallel walls.

- Varicose bronchiectasis displays irregular, beaded patterns resembling varicose veins.

- Cystic bronchiectasis presents with balloon-like sacs, indicating severe destruction.

- Mixed patterns frequently occur within the same patient’s lungs

- Distribution patterns throughout your lungs can indicate underlying causes

| Morphological Type | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Cylindrical (Tubular) | Intermediate severity; irregular beaded appearance; alternating dilated and regular segments; resembles varicose veins; moderate symptom burden |

| Varicose | Upper lobe predominance suggests CF or TB; lower lobe suggests aspiration or immunodeficiency; central airways suggest ABPA. |

| Cystic (Saccular) | Most severe form; balloon-like sacs; extensive structural destruction; frequently mucus-filled; associated with frequent exacerbations and complications |

| Mixed Patterns | Different morphological types in different lung regions; common in advanced disease; requires a comprehensive treatment approach.h |

| Distribution Clues | Upper lobe predominance suggests CF or TB; lower lobe suggests aspiration or immunodeficiency; central airways suggest ABPA |

Cylindrical Bronchiectasis

When you receive a diagnosis of cylindrical bronchiectasis, you’re experiencing the most common morphological pattern, accounting for approximately 60-70% of all bronchiectasis cases. Your airways show uniform widening while maintaining relatively parallel walls as they extend toward the periphery of your lung. On your CT scan, radiologists identify this pattern by measuring the broncho-arterial ratio- the diameter of your bronchus compared to its accompanying pulmonary artery. Typically, these structures maintain roughly equal diameters, but in cylindrical bronchiectasis, your bronchi measure 1.5 times or greater than the adjacent artery.

Demographic Considerations

Your risk of developing bronchiectasis varies significantly based on demographic factors that researchers have only recently begun to fully appreciate. Large-scale epidemiological studies reveal that bronchiectasis does not affect populations uniformly; instead, distinct patterns emerge across age groups, sexes, geographic regions, and socioeconomic strata. Understanding these patterns helps explain why some communities face disproportionate disease burdens and why diagnosis rates vary so dramatically between different healthcare systems.

These demographic variations reflect complex interactions between genetic predisposition, environmental exposures, healthcare access, and underlying disease prevalence. While bronchiectasis can develop at any stage of life and affects people of all backgrounds, recognising who faces elevated risk allows for earlier detection, more targeted screening in high-risk populations, and better allocation of healthcare resources. The demographic profile of bronchiectasis patients has also shifted over recent decades as diagnostic capabilities have improved and the underlying causes of the condition have evolved.

Age and Sex Distribution

Bronchiectasis prevalence increases dramatically with age, making it predominantly a condition of older adults in developed countries. Studies consistently show that prevalence rates begin rising after age 50 and accelerate sharply after age 70. In the United States, prevalence among adults aged 75 and older is approximately 1,106 per 100,000, more than five times the rate among adults aged 18-34. European data mirrors this pattern, with German studies reporting prevalence rates exceeding 1,500 per 100,000 in individuals aged 80 years or older. This age-related increase reflects cumulative exposure to respiratory infections, environmental insults, and age-associated immune dysfunction that collectively raise your risk of developing irreversible airway damage over time.

Women face significantly higher bronchiectasis rates than men across virtually all age groups, though the reasons for this sex disparity remain incompletely understood. Population studies across multiple countries report female-to-male ratios ranging from 1.3:1 to 2:1, with the gap widening with age. In the United States, women account for approximately 63% of cases of bronchiectasis. Several hypotheses attempt to explain this phenomenon: women may have anatomically narrower airways that are more susceptible to damage, hormonal factors might influence immune responses to respiratory infections, or women may seek medical care more frequently, leading to higher diagnosis rates. Additionally, specific conditions that cause bronchiectasis, including nontuberculous mycobacterial infection and autoimmune diseases, themselves show strong female predominance, which may partially account for the overall sex difference.

Geographic and Ethnic Variations

Bronchiectasis prevalence varies dramatically across geographic regions, with rates in some countries exceeding those in others by factors of ten or more. The highest documented prevalence comes from Finland, where studies report rates approaching 2,000 per 100,000 population, nearly three times the global average. New Zealand also shows elevated rates, particularly among Indigenous Māori and Pacific Islander populations, where childhood respiratory infections remain more common. Conversely, many low- and middle-income countries report lower prevalence figures, though these are likely to reflect underdiagnosis rather than a genuinely lower disease burden. In regions where access to high-resolution CT scanning is limited, bronchiectasis frequently goes undetected or is misdiagnosed as chronic bronchitis or treatment-resistant asthma.

Ethnic disparities in the prevalence and outcomes of bronchiectasis are substantial and concerning. In the United States, studies demonstrate that Asian and Pacific Islander populations have the highest prevalence rates-approximately 30% higher than non-Hispanic white populations, followed by Hispanic and Black populations. These disparities persist even after adjusting for socioeconomic factors, suggesting that genetic susceptibility, cultural practices, or environmental exposures specific to certain ethnic groups may play essential roles. Indigenous populations in multiple countries face disproportionate bronchiectasis burdens: Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children experience bronchiectasis rates up to 1,500 times higher than non-Indigenous Australian children, primarily driven by severe and recurrent respiratory infections in early childhood.

The geographic distribution of specific causes of bronchiectasis also varies considerably. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections show striking regional clustering.

Risk Factors and Aetiology

Understanding what causes bronchiectasis is necessary for both prevention and treatment, yet identifying the underlying aetiology can be remarkably challenging. In approximately 40-50% of cases, no specific cause is ever identified despite thorough investigation, a situation clinicians term ‘idiopathic bronchiectasis.’ This high proportion of unexplained cases reflects both the complexity of the disease and the reality that many causative events may have occurred years or even decades before diagnosis, leaving few investigative clues. For the remaining cases where aetiology can be determined, the causes fall into several broad categories:

The most commonly identified risk factors include prior severe respiratory infections (particularly in childhood), immune system disorders, genetic conditions like cystic fibrosis, chronic aspiration, and underlying inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease. Environmental exposures also play a significant role-tobacco smoke, occupational dust exposure, and air pollution all increase your risk. Specific anatomical abnormalities present from birth can predispose airways to damage, while allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA)-an exaggerated immune response to fungal spores-accounts for approximately 1-8% of cases. Any comprehensive diagnostic evaluation should systematically investigate these potential causes, as identifying an underlying aetiology can fundamentally change management strategies and potentially prevent progression.

Smoking and COPD

The relationship between smoking and bronchiectasis is both direct and indirect, creating multiple pathways to airway damage. Direct effects include impairment of mucociliary clearance. Cigarette smoke paralyses the cilia that usually sweep mucus from your airways, allowing secretions to accumulate and bacteria to colonise. Smoking also triggers chronic inflammation, weakens your immune response to respiratory pathogens, and damages the structural proteins that maintain airway integrity. Studies show that current smokers have significantly higher rates of bronchiectasis than never-smokers, with risk correlating to pack-year history. Even more concerning, bronchiectasis progresses more rapidly in those who continue smoking after diagnosis, with faster decline in lung function and more frequent exacerbations.

The overlap between COPD and bronchiectasis represents an increasingly recognised phenomenon that complicates both conditions. Research indicates that 25-50% of patients with moderate to severe COPD also have radiographic evidence of bronchiectasis when CT scans are performed. This coexistence isn’t coincidental-both conditions share common risk factors (particularly smoking), and the airflow obstruction and mucus retention characteristic of COPD create conditions favourable for developing bronchiectasis. When you have both conditions simultaneously, your prognosis worsens considerably: COPD patients with coexistent bronchiectasis experience more frequent exacerbations, higher rates of hospitalisation, faster lung function decline, and increased mortality compared to those with COPD alone. Any patient with COPD who experiences frequent exacerbations or produces significant daily sputum should be evaluated for possible underlying bronchiectasis.

Post-Infectious Bronchiectasis

Severe respiratory infections remain one of the most common identifiable causes of bronchiectasis worldwide, particularly in developing countries. The mechanism is straightforward but devastating: serious lung infections cause intense inflammation that damages airway walls, destroys the ciliated epithelium, and weakens structural support. If this damage is severe enough, the airways dilate permanently. Childhood infections pose a particular risk because developing lungs are more vulnerable to lasting damage. Historically, diseases like measles, pertussis (whooping cough), and tuberculosis were significant causes of post-infectious bronchiectasis. While vaccination programs have reduced these risks in developed nations, they remain significant factors globally. In adults, severe pneumonia, particularly necrotising pneumonia caused by organisms like Staphylococcus aureus or Klebsiella result in bronchi

Secondary Causes of Bronchiectasis

While post-infectious bronchiectasis remains the most commonly identified cause, accounting for approximately 30-40% of cases, a wide array of underlying conditions can trigger the airway damage that characterises this disease. Understanding these secondary causes matters enormously for your treatment plan-identifying and addressing the root cause can prevent further progression and guide targeted therapies. The international community has recognised the importance of understanding the causes of bronchiectasis, with initiatives like World Bronchiectasis Day (July 1) helping raise awareness of this complex condition.

Secondary bronchiectasis develops when an identifiable underlying disorder compromises your airways’ defence mechanisms. These conditions fall into several broad categories: genetic disorders affecting ciliary function or mucus properties; immune system deficiencies that impair bacterial clearance; inflammatory conditions that damage airway walls; and mechanical obstructions that prevent normal mucus drainage. Identifying these causes often requires systematic investigation, as many patients with secondary bronchiectasis initially receive their underlying diagnosis only after bronchiectasis symptoms prompt medical evaluation. The distribution pattern of bronchiectasis on your CT scan can provide valuable clues-upper lobe predominance might suggest cystic fibrosis or allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. At the same time, diffuse involvement could indicate immunodeficiency or a ciliary disorder.

Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) represents one of the most important genetic causes of bronchiectasis, affecting approximately 1 in 15,000 to 1 in 20,000 individuals. In PCD, genetic mutations disrupt the structure or function of cilia, microscopic hair-like structures that sweep mucus out of your airways. More than 50 different genes have been linked to PCD, each affecting other components of ciliary structure. When your cilia can’t beat properly or beat in an uncoordinated fashion, mucus accumulates in your airways from birth, setting the stage for recurrent infections and progressive bronchiectasis that typically begins in childhood.

The clinical presentation of PCD often provides diagnostic clues that distinguish it from other causes of bronchiectasis. Approximately 50% of PCD patients have Kartagener syndrome, a triad of bronchiectasis, chronic sinusitis, and situs inversus (mirror-image reversal of internal organs). Many PCD patients experience symptoms from birth, including neonatal respiratory distress, year-round, daily wet cough, and chronic ear and sinus infections. Fertility problems are common in adults with PCD, as sperm tails and fallopian tube cilia share structural similarities with airway cilia. Diagnosis requires specialised testing, including nasal nitric oxide measurement (characteristically very low in PCD), high-speed video microscopy of ciliary beat pattern, and genetic testing. Early diagnosis and aggressive airway clearance therapy can significantly slow bronchiectasis progression in PCD patients, making identification of this condition particularly valuable.

Immunodeficiency Disorders

Your immune system serves as the frontline defence against the bacteria that constantly enter your airways with each breath. When components of this defence system malfunction, recurrent or persistent respiratory infections can lead to progressive bronchiectasis. Immunodeficiency disorders represent the identifiable cause in approximately 5-10% of bronchiectasis cases, though this percentage rises significantly in patients with severe or early-onset disease. The most common immunodeficiency associated with bronchiectasis is Common Variable Immunodeficiency (CVID), which typically presents in the second to fourth decade of life with recurrent sinopulmonary infections. However, it can appear at any age.

CVID affects approximately 1 in 25,000 to 1 in 50,000 people and is characterised by low levels of immunoglobulins (antibodies)-particularly IgG and IgA-which are necessary for fighting bacterial infections. Many CVID patients experience years of recurrent respiratory infections.

Underlying Pathologies

Understanding what caused your bronchiectasis matters for several reasons. First, identifying the underlying cause can fundamentally change your treatment approach. Some causes are treatable or reversible if caught early enough. Second, certain underlying conditions require specific monitoring or therapies beyond standard bronchiectasis management. Third, knowing the cause helps predict disease progression and potential complications. Yet despite extensive investigation, approximately 40-50% of bronchiectasis cases remain ‘idiopathic’-meaning no definitive cause can be identified. This doesn’t mean these cases lack a cause; rather, current diagnostic tools may be insufficient, the original insult may have occurred decades earlier and left no trace, or multiple subtle factors may have combined in ways we don’t yet fully understand.

The identifiable causes of bronchiectasis span a remarkably diverse range, from genetic disorders present at birth to infections acquired in adulthood. Post-infectious bronchiectasis historically represented the most common form, typically following severe pneumonia, whooping cough, or tuberculosis in childhood. While childhood vaccination programs have reduced this in developed countries, it remains a significant cause globally. Immunodeficiency disorders account for approximately 5-10% of cases, with conditions like common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) leaving you unable to produce adequate antibodies against respiratory pathogens. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA)-an exaggerated immune response to Aspergillus fungus-causes bronchiectasis in susceptible individuals, particularly those with asthma or cystic fibrosis. Genetic conditions, most notably cystic fibrosis and primary ciliary dyskinesia, produce characteristic patterns of bronchiectasis through distinct mechanisms affecting mucus properties or ciliary function.

Autoimmune and Connective Tissue Diseases

Your immune system, designed to protect you, can sometimes turn against your own tissues-and when it does, your lungs may become collateral damage. Rheumatoid arthritis carries an influential association with bronchiectasis, with studies showing that 3-30% of RA patients develop the condition compared to less than 1% of the general population. This wide range reflects differences in how carefully researchers looked and which populations they studied, but the connection is undeniable. Interestingly, the relationship appears bidirectional: bronchiectasis can precede arthritis symptoms by years, suggesting shared underlying mechanisms rather than a simple cause-and-effect relationship. Sjögren’s syndrome, characterised by dry eyes and mouth due to immune-mediated destruction of moisture-producing glands, also affects the airways’ mucus-producing cells, creating conditions favourable for the development of bronchiectasis. The chronic inflammation in these autoimmune conditions doesn’t just damage joints and glands-it creates a pro-inflammatory environment throughout your body, including your airways.

Inflammatory bowel diseases, particularly ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, show unexpected pulmonary connections. Between 0.4% and 3.9% of IBD patients develop bronchiectasis, a rate significantly higher than that of the general population. The mechanism isn’t entirely clear, but theories include shared genetic susceptibility, immune dysregulation affecting both the gut and the lungs, or the migration of activated immune cells from intestinal tissue to the airways. Systemic lupus erythematosus, though better known for kidney and joint involvement, can cause a range of pulmonary complications, including bronchiectasis. What makes autoimmune-associated bronchiectasis particularly challenging is timing: the lung damage may develop silently while your rheumatologist focuses on controlling joint symptoms, or it may emerge as a side effect of immunosuppressive medications that increase infection risk. This is why respiratory symptoms in patients with autoimmune diseases deserve thorough investigation rather than dismissal as “just another manifestation” of the underlying condition.

Nontuberculous Mycobacteria

Nontuberculous mycobacteria represent one of the most complex and controversial aspects of bronchiectasis-are they cause, consequence, or both? NTM are environmental organisms found worldwide in water, soil, and dust. Unlike tuberculosis, they don’t spread person-to-person, and most people encounter them regularly without consequence. However, NT

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical picture of bronchiectasis varies considerably from person to person, ranging from minimal symptoms that barely interfere with daily life to severe, disabling respiratory compromise. Your symptom burden typically correlates with the extent of bronchial damage, the presence and type of bacterial colonisation, and how frequently you experience exacerbations. Some patients remain relatively stable for years with appropriate management, while others experience progressive decline despite optimal treatment. Understanding the spectrum of clinical manifestations helps you recognise disease progression early and communicate effectively with your healthcare team about changes in your condition.

The hallmark feature that distinguishes bronchiectasis from other chronic respiratory conditions is persistent sputum production, often described as the defining characteristic that should prompt investigation for the disease. Unlike the occasional mucus production that accompanies a common cold, bronchiectasis typically causes daily expectoration that continues month after month, year after year. The pattern, volume, and characteristics of this sputum provide valuable clinical information about disease activity and can signal when your condition is worsening or when new bacterial infections have taken hold.

Common Symptoms of Bronchiectasis

Chronic productive cough affects approximately 90% of people with bronchiectasis and represents the most common presenting symptom. You may find yourself coughing up sputum daily, with volumes ranging from a teaspoon to several tablespoons. The sputum is typically thick and sticky, requiring effort to expectorate, and its colour provides diagnostic clues: clear or white mucus suggests relatively stable disease, yellow or green indicates active bacterial infection, and brown colouration may signal old blood or specific bacterial species like Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Many patients describe their most productive coughing occurring in the morning, when overnight mucus accumulation drains from the dilated airways as you change position after sleeping. This pattern becomes so routine that some people incorporate extended morning coughing sessions into their daily schedule, timing their awakening to allow for airway clearance before other activities.

Breathlessness (dyspnea) develops in 60-70% of patients, though its severity varies widely depending on disease extent and your baseline lung function. Initially, you might notice shortness of breath only during vigorous exertion, such as climbing stairs or hurrying to catch a bus. As bronchiectasis progresses, the threshold for breathlessness typically lowers-you may become winded during routine activities like showering, dressing, or walking short distances. This symptom results from multiple factors: mucus plugging reduces the number of functional airways available for gas exchange, chronic inflammation damages lung tissue, and the work of breathing increases as your respiratory muscles labour to move air through narrowed, obstructed passages. Fatigue accompanies breathlessness in most cases, reflecting both the increased energy expenditure required for breathing and the systemic effects of chronic inflammation. Chest pain affects roughly 20-30% of patients, usually described as a dull ache or tightness rather than sharp pain. However, pleuritic chest pain (sharp pain worsened by deep breathing) can occur if inflammation extends to the pleural lining surrounding your lungs.

Physical Signs Upon Examination

When your physician examines you, several characteristic physical findings may indicate bronchiectasis, though their absence doesn’t rule out the condition, particularly in mild or early disease. Crackles (formerly called rales) represent the most common examination finding, detected in 60-75% of patients during chest auscultation. These sounds occur when your doctor listens with a stethoscope and hears discontinuous popping or clicking noises as air moves through airways containing secretions or as collapsed small airways suddenly open during inspiration. The crackles in bronchiectasis typically have a distinctive quality: they’re often described as “coarse” rather than acceptable, may be heard during both inspiration and expiration, and characteristically change or clear temporarily after you cough, a feature that helps distinguish bronchiectasis from other conditions like pulmonary fibrosis, where crackles persist unchanged despite coughing.

Wheezing, a high-pitched whistling sound during breathing, occurs in approximately 30-40% of patients and reflects airway narrowing from mucus accumulation,

Diagnostic Approaches

Reaching an accurate diagnosis of bronchiectasis requires a systematic approach that combines clinical assessment, imaging confirmation, and investigation of underlying causes. The average delay between symptom onset and diagnosis ranges from 4 to 6 years, partly because symptoms often overlap with more common respiratory conditions like asthma or COPD. Your physician will typically suspect bronchiectasis based on your clinical history, particularly if you report chronic productive cough, recurrent chest infections, or persistent sputum production. However, clinical suspicion alone cannot confirm the diagnosis. The structural changes defining bronchiectasis must be documented by imaging, and once confirmed, a thorough investigation should follow to identify any treatable underlying causes.

Modern diagnostic protocols emphasise a three-stage approach: first, confirming the presence of bronchiectasis through imaging; second, assessing disease severity and extent; and third, investigating potential aetiologies. This comprehensive evaluation is crucial because identifying and treating an underlying cause can fundamentally alter your disease trajectory and prevent progression. Studies show that approximately 60-70% of cases can be linked to an identifiable cause when thorough investigation is performed, yet many patients receive only imaging confirmation without further workup. This represents a missed opportunity, as certain underlying conditions-such as immunodeficiency, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, or gastroesophageal reflux-respond well to targeted interventions that can slow or even halt disease progression.

Imaging: The Gold Standard

High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest is the definitive test for diagnosing bronchiectasis, having replaced bronchography (an older technique involving contrast dye injection) as the gold standard in the 1980s. HRCT provides detailed cross-sectional images of your lungs, allowing radiologists to visualise airway dilation and wall thickening with remarkable precision. The classic radiological signs include the “signet ring sign”-where a dilated bronchus appears larger than its accompanying blood vessel, resembling a signet ring when viewed in cross-section- and the “tramline sign,” where parallel thickened bronchial walls appear as two lines running alongside each other. Your HRCT will typically be performed without contrast and uses thin slices (1-1.5mm) to capture fine anatomical detail. The scan not only confirms the diagnosis but also reveals the distribution pattern (focal versus diffuse), morphological type (cylindrical, varicose, or cystic), and extent of involvement across different lung lobes.

Chest X-rays, while commonly performed as an initial investigation, miss bronchiectasis in up to 50% of cases, particularly when the disease is mild or limited to specific lung regions. On plain radiography, bronchiectasis may appear as increased lung markings, tramlines, or ring shadows, but these findings are neither sensitive nor specific. Some patients discover their bronchiectasis incidentally when undergoing CT scanning for unrelated reasons-a phenomenon that has become more common as CT imaging has proliferated in medical practice. The timing of your HRCT matters; ideally, it should be performed when you’re clinically stable rather than during an acute exacerbation, as acute inflammation can temporarily worsen airway appearance and potentially lead to overestimation of disease severity. However, if your initial scan was performed during an exacerbation, your physician may not recommend repeat imaging once you are stable, as the diagnosis rarely changes.

Aetiological Investigation

Once bronchiectasis is confirmed on imaging, your physician should initiate a systematic search for underlying causes-a process that international guidelines recommend for all patients with newly diagnosed disease. The basic aetiological workup typically includes complete blood count, serum immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, IgM, and IgE), testing for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), and sputum culture to identify chronic bacterial colonisation or nontuberculous mycobacterial infection. Many centres also perform testing for specific antibody responses to pneumococcal vaccines, as inadequate antibody production may indicate functional immunodeficiency even when total immunoglobulin levels appear normal. Depending on your clinical presentation and initial test

Management Strategies

Effective management of bronchiectasis requires a comprehensive, individualised approach that targets multiple components of the vicious vortex simultaneously. Your treatment plan should address infection control, inflammation reduction, airway clearance, and the prevention of exacerbations, with the specific combination and intensity of therapies tailored to your disease severity, symptom burden, and underlying cause. Unlike conditions such as asthma or COPD, where standardised treatment algorithms dominate clinical practice, bronchiectasis management demands flexibility and frequent reassessment. What works during stable periods may need adjustment during exacerbations, and your regimen will likely evolve as researchers continue to develop evidence-based approaches for this historically understudied condition.

The cornerstone principle guiding modern bronchiectasis care is interrupting the vicious vortex at multiple points. Studies consistently demonstrate that patients who engage in regular airway clearance, receive appropriate antimicrobial therapy when needed, and address underlying causes experience fewer exacerbations, better quality of life, and slower disease progression compared to those receiving minimal intervention. A 2019 study published in the European Respiratory Journal found that comprehensive management programs reduced exacerbation frequency by 35-50% and decreased hospitalisations by nearly 60%. Your healthcare team should include not just your primary pulmonologist, but potentially respiratory physiotherapists, infectious disease specialists, and, depending on your underlying cause, immunologists or rheumatologists who can address the full spectrum of factors contributing to your condition.

Treating the Underlying Cause

Identifying and addressing the root cause of your bronchiectasis represents the most direct path to slowing or potentially halting disease progression. For approximately 30-40% of patients, a specific treatable underlying condition can be identified, and targeting this cause can dramatically alter the disease trajectory. If you have an immunoglobulin deficiency, for example, regular immunoglobulin replacement therapy can reduce infection frequency by 60-90%, substantially decreasing the inflammatory burden on your airways. Similarly, if allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) caused your bronchiectasis, antifungal medications combined with corticosteroids can prevent further allergic inflammation and halt progression. Patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency may benefit from augmentation therapy, while those with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) often see improvement with aggressive acid suppression or anti-reflux surgery.

The challenge lies in the reality that many patients have idiopathic bronchiectasis, meaning no underlying cause can be identified despite thorough investigation. Even in these cases, don’t assume nothing can be done about causation. Emerging research suggests that previously unrecognised immune defects, genetic variations, or environmental exposures may explain many ‘idiopathic’ cases. Your pulmonologist should conduct a comprehensive etiological workup, including immunoglobulin levels, specific antibody responses to vaccines, alpha-1 antitrypsin levels, and autoimmune markers, and consider genetic testing for conditions such as cystic fibrosis or primary ciliary dyskinesia. A 2022 study demonstrated that extended immunological testing identified previously missed immune deficiencies in 18% of patients initially labelled as having idiopathic disease. These patients subsequently received targeted immunomodulatory therapies that significantly improved their clinical outcomes, underscoring the importance of thorough investigation rather than premature acceptance of an idiopathic diagnosis.

Airway Clearance: The Foundation of Management

Regardless of what caused your bronchiectasis or how severe it is, airway clearance therapy (ACT) forms the absolute foundation of your daily management regimen. Since impaired mucociliary clearance sits at the heart of the vicious vortex, helping your lungs expel accumulated mucus addresses the problem at its source. Regular, adequate airway clearance reduces bacterial load, decreases inflammation, improves lung function, and most importantly, reduces exacerbation frequency. A landmark 2018 systematic review analysing 21 randomised controlled trials concluded that patients performing daily ACT experienced significant improvements in quality of life scores, reduced sputum volume, and fewer acute exacerbations compared to those who didn’t engage in regular.

Pharmacological Interventions

Managing bronchiectasis requires targeting multiple components of the vicious vortex simultaneously. While the structural damage to your airways cannot be reversed, the right pharmacological approach can significantly slow disease progression, reduce exacerbations, and improve your quality of life. Treatment strategies have evolved considerably over the past decade, moving from purely symptomatic relief toward more comprehensive approaches that address the underlying disease mechanisms. The goal is not simply to make you feel better temporarily, but to interrupt the cycle of infection and inflammation that drives progressive lung damage.

Your treatment plan will likely combine several medication classes, each addressing different aspects of the disease. Studies show that patients who adhere to comprehensive treatment protocols experience 30-50% fewer exacerbations compared to those receiving minimal intervention. The specific medications you receive will depend on your disease severity, the bacteria colonising your airways, your symptom burden, and how frequently you experience exacerbations. International guidelines now recommend a personalised approach, with treatment intensity scaled to match your individual disease characteristics and risk factors.

Antibiotic Therapy

Antibiotics form the cornerstone of bronchiectasis management, addressing the chronic bacterial infection that perpetuates airway inflammation and damage. You’ll encounter antibiotics in three distinct contexts: treatment of acute exacerbations, eradication of newly detected pathogens, and long-term suppressive therapy. During exacerbation periods, when your symptoms worsen significantly, you’ll typically receive a 14-day course of oral antibiotics targeting the bacteria most commonly found in your sputum cultures. Common choices include amoxicillin-clavulanate for Haemophilus influenzae, ciprofloxacin for Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and clarithromycin or azithromycin for various organisms. The specific antibiotic your physician prescribes should ideally be guided by sputum culture results rather than empirical guessing, as targeted antibiotic therapy achieves clinical success rates of 75-85% compared to 50-60% for empirical treatment.

Long-term antibiotic therapy represents a more controversial but increasingly common approach, particularly if you experience three or more exacerbations per year or have chronic Pseudomonas colonisation. Two main strategies exist: continuous oral macrolides (typically azithromycin 250-500mg three times weekly) and intermittent inhaled antibiotics. Azithromycin offers both antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects, with landmark trials demonstrating a 50% reduction in exacerbation frequency. Inhaled antibiotics-particularly tobramycin, colistin, and gentamicin-deliver high drug concentrations directly to your airways while minimising systemic side effects. These are typically administered on an alternating schedule (28 days on, 28 days off) and are especially valuable for patients with Pseudomonas infections. However, long-term antibiotic use carries risks, including bacterial resistance, aminoglycoside-induced hearing impairment, and macrolide-induced cardiac arrhythmias, necessitating careful monitoring and regular reassessment of whether benefits continue to outweigh risks.

Bronchodilators

Bronchodilators work by relaxing the smooth muscle surrounding your airways, allowing them to open more widely and facilitating easier breathing and mucus clearance. Approximately 40-50% of bronchiectasis patients demonstrate significant airflow obstruction that responds to bronchodilator therapy, particularly those with coexisting asthma or COPD. The two main classes-beta-2 agonists (such as albuterol or salbutamol for short-term relief, and salmeterol or formoterol for long-acting control) and anticholinergics (like ipratropium or tiotropium)-can be used individually or in combination, depending on your response. If spirometry testing shows that your FEV1 (forced expiratory volume) improves by 12% or more after bronchodilator administration, you’re likely to benefit from regular use of these medications.

The evidence supporting the use of bronchodilators specifically for bronchiectasis remains.

Surgical Considerations

For most patients with bronchiectasis, medical management remains the cornerstone of treatment. However, surgical intervention becomes a viable option when your disease is localised to a specific area of the lung and when medical therapy has failed to control symptoms adequately. Surgery for bronchiectasis has evolved considerably over the past several decades, shifting from extensive procedures performed in the pre-antibiotic era to more refined, targeted interventions reserved for carefully selected patients. Studies suggest that 5-10% of patients with bronchiectasis may benefit from surgical evaluation, though actual surgical rates vary considerably across healthcare systems and geographic regions.

Your candidacy for surgery depends on multiple factors that your respiratory physician and thoracic surgeon will carefully assess together. The decision to proceed with surgical treatment represents a balance between the potential benefits of removing diseased lung tissue, which serves as a reservoir for chronic infection and inflammation, and the inherent risks of thoracic surgery. Modern imaging techniques, particularly high-resolution CT scanning, have dramatically improved our ability to precisely delineate the extent and distribution of bronchiectatic changes, enabling more accurate patient selection than ever before. The goal of surgery in bronchiectasis is not simply to remove damaged tissue, but to improve your quality of life by reducing symptom burden, decreasing exacerbation frequency, and potentially slowing overall disease progression.

Indications for Surgical Intervention

Your physician may recommend surgical evaluation if you have localised bronchiectasis confined to one lobe or segment of your lung, particularly when this area produces the majority of your symptoms despite optimal medical therapy. Specific indications include: recurrent severe infections requiring multiple hospitalisations or intravenous antibiotics, massive or recurrent hemoptysis (coughing up blood) that threatens your life or significantly impairs your quality of life, and persistent symptoms such as productive cough and purulent sputum production that remain uncontrolled despite comprehensive medical management, including airway clearance techniques, inhaled therapies, and appropriate antibiotic treatment. Surgery may also be considered when a specific lobe or segment shows progressive deterioration with increasing infection frequency, even if other areas of your lungs remain relatively preserved.

Additional considerations that strengthen the case for surgical intervention include young age and good overall health status, absence of significant comorbidities that would increase surgical risk, and, importantly, adequate pulmonary reserve, meaning your remaining lung tissue has sufficient function to maintain respiratory capacity after the diseased portion is removed. Patients with cystic bronchiectasis or those with destroyed, non-functional lung segments that serve primarily as infection reservoirs often derive the most significant benefit from surgery. Conversely, surgery is generally contraindicated if you have widespread bilateral disease affecting multiple lobes, poor underlying lung function with FEV1 less than 40% predicted, significant cardiovascular disease, or active infection with organisms like Pseudomonas aeruginosa in areas beyond the proposed resection site. The presence of conditions like cystic fibrosis or primary ciliary dyskinesia, which typically cause diffuse disease, usually makes you a poor surgical candidate since removing one area does not address the systemic nature of airway dysfunction.

Types of Surgical Procedures

Several surgical approaches are available depending on the extent and location of your bronchiectatic disease:

- Segmentectomy: Removal of one or more bronchopulmonary segments, preserving as much healthy lung tissue as possible

- Lobectomy: Complete removal of an entire lobe, the most commonly performed procedure for localised bronchiectasis

- Bilobectomy: Removal of two lobes, typically performed when adjacent lobes are both significantly diseased

- Pneumonectomy: Complete removal of an entire lung, reserved for extensive unilateral disease when lesser resections would be inadequate

- Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS): Minimally invasive approach using small incisions and camera guidance, associated with reduced postoperative pain an

Understanding Disparities in Care

Access to appropriate bronchiectasis care varies dramatically depending on where you live, your socioeconomic status, and even your gender. Studies consistently show that patients in rural areas wait an average of 7-10 years between symptom onset and accurate diagnosis, compared to 3-5 years for those in urban centres

With academic medical facilities. This diagnostic delay has profound consequences-each year without proper treatment allows the vicious vortex to continue unchecked, leading to more extensive lung damage that becomes increasingly difficult to manage. Geographic disparities extend beyond diagnosis to ongoing care: patients living more than 50 miles from a specialist pulmonology centre experience significantly higher rates of hospitalisation for exacerbations and have reduced access to vital treatments like airway clearance physiotherapy.

Gender disparities present another troubling dimension of inequitable care. Despite bronchiectasis affecting women more frequently than men (with female-to-male ratios ranging from 1.3:1 to 2:1 in most populations), women wait longer for diagnosis and are less likely to receive guideline-concordant treatment. Research from the UK Bronchiectasis Registry revealed that women were 23% less likely than men to be prescribed long-term macrolide antibiotics when clinically indicated, and were referred to specialist centres at lower rates despite having similar or greater disease severity. Socioeconomic factors compound these disparities: patients from lower-income backgrounds have fewer opportunities for daily airway clearance sessions that form the cornerstone of bronchiectasis management, often because they cannot afford the necessary equipment or take time off work for physiotherapy appointments. - Why Such Disparity?

- The roots of these care disparities lie partly in bronchiectasis’s historical status as an ‘orphan disease.’ Unlike asthma or COPD, bronchiectasis lacks widespread awareness among both healthcare providers and the general public, leading to misdiagnosis or delayed recognition of symptoms. Many primary care physicians encounter only a handful of cases of bronchiectasis throughout their careers, leaving them unfamiliar with its presenting features and appropriate diagnostic pathways. This knowledge gap becomes particularly problematic in resource-limited settings where access to high-resolution CT scanning, the gold standard for diagnosis, may be restricted or require lengthy waiting periods. A 2023 survey of general practitioners across five countries found that only 38% felt confident diagnosing bronchiectasis, and fewer than half were aware of current management guidelines.

The healthcare system structures themselves create barriers to equitable care. Bronchiectasis management requires coordinated input from multiple specialists-pulmonologists, infectious disease physicians, physiotherapists, and sometimes immunologists or geneticists- yet fragmented healthcare systems often lack the infrastructure to provide this integrated approach. Patients in countries without universal healthcare face additional financial barriers: the annual cost of bronchiectasis treatment can exceed $50,000 when accounting for medications, physiotherapy, imaging, and hospitalisations. Even in countries with public healthcare systems, variations in what services are covered create a patchwork of access. Some regions provide subsidised airway clearance devices and home physiotherapy. In contrast, others require patients to pay out of pocket for these vital interventions, effectively rationing care based on ability to pay rather than clinical need. - Barriers to Effective Management

Beyond access to diagnosis and specialist care, patients face substantial obstacles in adhering to the demanding treatment regimens required for bronchiectasis. Optimal management typically involves 30-60 minutes of daily airway clearance therapy, multiple inhaled medications, regular sputum monitoring, and frequent follow-up appointments- a burden that proves overwhelming for many patients, particularly those juggling work responsibilities, caregiving duties, or managing multiple chronic conditions simultaneously. Research shows that adherence to prescribed airway clearance regimens averages only 40-50%, not because patients don’t understand its importance, but because the time commitment and physical demands make consistent compliance extremely challenging. The psychological toll of managing a chronic, progressive lung disease compounds these practical barriers, with depression and anxiety affecting approximately 30-40% of bronchiectasis patients and further reducing treatment adherence.

Healthcare literacy represents another significant barrier that disproportionately affects disadvantaged populations. Bronchiectasis management requires patients to recognise subtle - Future Directions in Bronchiectasis Management

The landscape of bronchiectasis treatment is undergoing its most significant transformation in decades. After years of relying primarily on symptom management and supportive care borrowed from other respiratory conditions, your treatment options are expanding with therapies specifically designed to target the underlying mechanisms of this disease. Clinical trials are currently evaluating more than a dozen novel agents, including anti-inflammatory medications, mucolytics, antimicrobials, and immunomodulators. This pipeline represents not just incremental improvements but potentially paradigm-shifting approaches that could fundamentally alter disease trajectories for millions of patients worldwide.

Research into the hidden epidemic of post-tuberculosis bronchiectasis has also highlighted the global dimensions of this condition, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where TB remains endemic. This growing recognition has spurred international collaborative efforts to develop more accessible diagnostic tools and treatment protocols. Precision medicine approaches are beginning to stratify patients based on their specific inflammatory profiles, bacterial colonisation patterns, and genetic factors, allowing for more targeted interventions. Your treatment plan in the coming years may look radically different from current standards, with therapies tailored to your individual disease phenotype rather than the one-size-fits-all approaches that have dominated care for generations. - The Path Forward

Healthcare systems worldwide are recognising that bronchiectasis requires dedicated clinical pathways and specialised expertise. Multidisciplinary bronchiectasis clinics are proliferating across Europe, North America, and Australia, bringing together pulmonologists, respiratory physiotherapists, specialist nurses, microbiologists, and pharmacists under one coordinated framework. These centres demonstrate that comprehensive, protocol-driven care can reduce exacerbation frequency by 30-50% compared with fragmented general respiratory care. Your access to such specialised services may significantly impact your long-term outcomes, with evidence suggesting that patients managed in dedicated bronchiectasis clinics experience fewer hospitalisations, better quality of life, and slower disease progression.

Digital health technologies are also reshaping how you might monitor and manage your condition. Smartphone applications now allow real-time symptom tracking, medication adherence monitoring, and early exacerbation detection through algorithms that analyse patterns in your reported symptoms, sputum characteristics, and even cough sounds. Wearable devices measuring oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, and physical activity levels provide continuous data streams that can alert your healthcare team to deterioration before you experience severe symptoms. Telemedicine platforms are extending specialist expertise to rural and underserved areas, while artificial intelligence systems are being trained to interpret chest CT scans with accuracy approaching that of experienced radiologists. These technological advances promise to democratize access to high-quality bronchiectasis care regardless of your geographic location. - Brensocatib and Other Pipeline Therapies

Brensocatib represents the most advanced investigational therapy specifically developed for bronchiectasis, targeting a novel mechanism in the inflammatory cascade. This oral medication inhibits dipeptidyl peptidase 1 (DPP-1), an enzyme that activates neutrophil serine proteases, destructive enzymes released by white blood cells that contribute to progressive airway damage. Phase 3 trial results published in 2024 showed that brensocatib reduced exacerbation rates by approximately 30% in patients with frequent exacerbations and chronic bacterial infection. Your treatment regimen could include this medication within the next few years if regulatory approvals proceed as anticipated, offering the first therapy to interrupt directly the inflammatory component of the vicious vortex.

Beyond brensocatib, several other promising candidates are advancing through clinical development. Colistimethate sodium delivered via a novel dry powder inhaler is being evaluated for the suppression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, with potentially better tolerability than nebulised formulations. Inhaled nitric oxide and gamma interferon are being tested for their ability to enhance bacterial killing and modulate immune responses in infected airways. Mucolytic agents are more potent than current options, including recombinant - Summing Up

Drawing together the evidence presented throughout this guide, you can see that bronchiectasis represents far more than a rare historical curiosity. Your understanding of this condition should now encompass its true scale-a hidden epidemic affecting hundreds of thousands in the United States alone and millions globally, with prevalence rates climbing approximately 8% annually. You’ve learned how the vicious vortex of infection, inflammation, impaired clearance, and structural damage creates a self-perpetuating cycle that, left unmanaged, progressively destroys your airways. The condition’s irreversible nature makes early detection and intervention particularly important for your long-term respiratory health.

As you move forward with this knowledge, you’re better equipped to recognise symptoms that might otherwise be dismissed as recurrent chest infections or persistent cough. Your awareness of bronchiectasis transforms you from a passive observer into an informed advocate, whether for your own health or that of someone you care about. The landscape of bronchiectasis management is evolving rapidly, with genuinely disease-modifying treatments poised to become available for the first time in the condition’s documented history. Your engagement with healthcare providers, armed with the understanding you’ve gained here, positions you to benefit from emerging therapies and evidence-based management strategies that can meaningfully slow progression, reduce exacerbations, and improve your quality of life despite this chronic condition.

What exactly happens to my lungs when I have bronchiectasis?

Bronchiectasis causes permanent widening and scarring of your airways (bronchi). Usually, your airways are lined with tiny hair-like structures called cilia that sweep mucus and trapped bacteria out of your lungs. When you have bronchiectasis, these damaged, stretched airways lose their ability to clear mucus effectively. Secretions pool in the dilated areas, creating an environment where bacteria multiply. This triggers inflammation, which further damages the airway walls, leading to even greater dilation. The process feeds on itself-infection causes inflammation, inflammation damages airways, damaged airways trap more mucus, and trapped mucus harbours more bacteria. This self-perpetuating pattern is why bronchiectasis tends to worsen over time without proper treatment, and why the damage, once established, cannot be reversed.

How is bronchiectasis different from COPD or chronic bronchitis?

While bronchiectasis, COPD, and chronic bronchitis can all cause coughing and mucus production, they are distinct conditions with different underlying mechanisms. COPD primarily involves destruction of the tiny air sacs (alveoli) where oxygen exchange occurs, along with narrowing of small airways due to inflammation. Chronic bronchitis is characterised by excessive mucus production and airway inflammation, but without the permanent structural changes seen in bronchiectasis. The hallmark of bronchiectasis is irreversible widening of the medium-sized airways visible on CT scans. However, these conditions can overlap; some people have both COPD and bronchiectasis, which generally leads to worse symptoms and outcomes. Accurate diagnosis matters because treatment approaches differ: bronchiectasis management focuses heavily on airway clearance techniques and the management of chronic infections, while COPD treatment emphasises bronchodilators and the management of airflow limitation.

Why wasn’t bronchiectasis detected earlier in my life if the damage is permanent?

Bronchiectasis frequently goes undiagnosed for years, sometimes decades, for several reasons. Early in the disease, symptoms may be mild or attributed to other common conditions like asthma, recurrent bronchitis, or smoking-related cough. Many primary care physicians have limited familiarity with bronchiectasis because it was historically considered rare. Standard chest X-rays often miss bronchiectasis entirely-a high-resolution CT scan is needed for definitive diagnosis, but this test isn’t routinely ordered unless there’s specific suspicion. Additionally, the condition develops gradually in most cases, so patients may adapt to slowly worsening symptoms without recognising them as abnormal. The recent increase in diagnosed cases reflects both genuine increases in prevalence and improved recognition by healthcare providers. If you’ve had recurrent chest infections, a chronic productive cough lasting months, or unexplained breathlessness, these may have been early signs that weren’t connected to a bronchiectasis diagnosis until imaging was performed.

Can bronchiectasis be cured, or will I have this condition forever?

The structural damage of bronchiectasis is permanent and cannot currently be reversed-the widened, scarred airways will not return to normal. In this sense, there is no cure. However, this doesn’t mean the condition is untreatable or that progression is inevitable. With appropriate management, many people with bronchiectasis maintain stable lung function and good quality of life for years or decades. Treatment focuses on breaking the infection-inflammation cycle through airway clearance techniques (to remove trapped mucus), antibiotics (to control bacterial infections), and sometimes anti-inflammatory medications. These interventions can significantly slow or even halt disease progression. The severity and progression of bronchiectasis vary enormously between individuals-some people have mild disease that barely impacts their daily life, while others experience frequent exacerbations requiring intensive treatment. Early diagnosis and consistent adherence to treatment regimens offer the best opportunity to prevent the condition from worsening and to minimise.

Its impact on your life.

What causes bronchiectasis, and could I have prevented it

Bronchiectasis has numerous potential causes, and in many cases, no single cause can be identified (termed “idiopathic” bronchiectasis). Common triggers include severe