How Adalimumab Works as a Dupuytren’s Disease – Early Treatment

Groundbreaking research into Dupuytren’s disease early treatment from Oxford University is finally offering a way to break the two-century cycle of surgery and recurrence. By targeting the cellular root cause before fingers begin to curl, researchers at the Kennedy Institute have demonstrated that a commonly available anti-inflammatory drug, Adalimumab (Humira), can halt the progression of early-stage nodules. This shift from “waiting for contracture” to active prevention marks a game-changing discovery for the 4% of the population living with this debilitating hand condition.

It’s not just about thick tissue

Think about it… If this were just about thick collagen bands, why would surgery have such high recurrence rates? Because we’ve been treating the symptom, not the underlying inflammatory process driving the whole thing.

Your doctor probably told you that Dupuytren’s contracture was basically a problem of overgrown tissue in your palm – like scar tissue gone haywire. That’s what medical textbooks have been saying for 200 years. However, new research reveals that Dupuytren’s is a localised inflammatory disorder, not merely a mechanical tissue problem. This fundamentally changes how we should think about treatment.

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways:

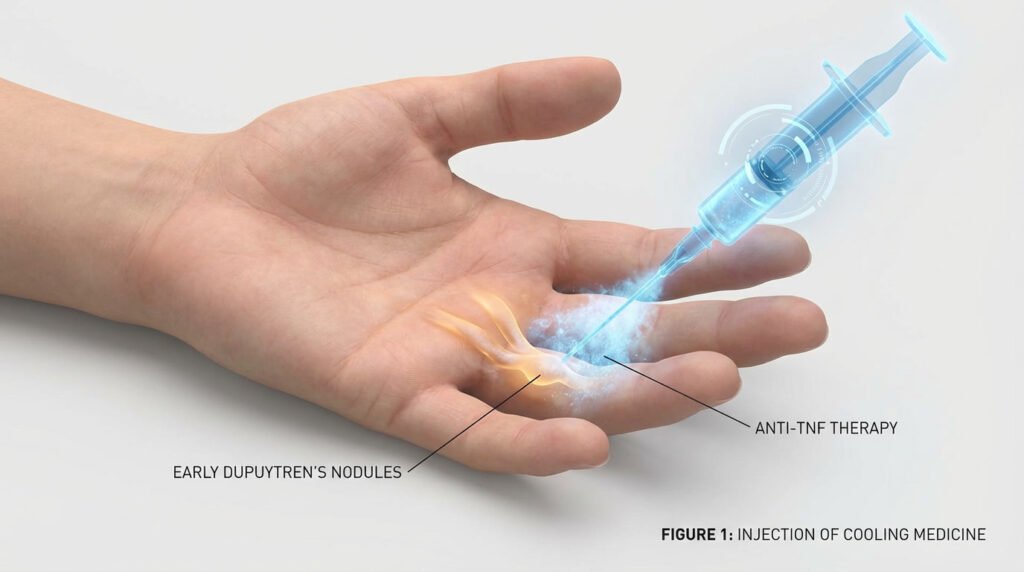

- Anti-TNF therapy represents the first preventive treatment for Dupuytren’s contracture in 200 years – instead of waiting for fingers to curl and then surgically releasing them (with recurrence rates up to 75%), Oxford researchers demonstrated that injecting adalimumab directly into early nodules can soften and shrink them before cords and contractures develop. The RIDD trial demonstrated statistically significant reductions in nodule hardness and size, with benefits persisting for 9 months after the final injection. This fundamentally changes the treatment paradigm from reactive intervention to proactive prevention.

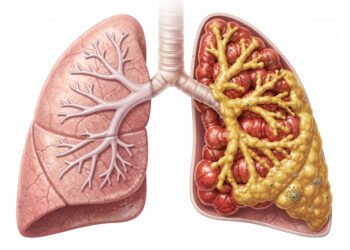

- The breakthrough came from identifying Dupuytren’s disease as a localised inflammatory disease driven by low TNF levels. Researchers discovered that immune cells in the palm secrete just enough TNF to convert normal fibroblasts into myofibroblasts (the cells that produce excessive collagen and contract your fingers). These myofibroblasts then secrete IL-33, which signals immune cells to keep producing TNF, creating a self-sustaining inflammatory loop. By blocking TNF with adalimumab, the treatment interrupts this cycle at its source rather than addressing the downstream consequences once they have formed.

- The treatment shows promise but isn’t ready for widespread use yet – while the 18-month results are encouraging with excellent safety profiles and no serious adverse events, Dupuytren’s progresses slowly over decades, and researchers acknowledge that 10+ years of follow-up data are needed to confirm whether preventing nodule growth actually prevents contractures and preserves hand function long-term. The therapy also only works for early-stage disease (nodules without established contractures), requires off-label use of an expensive medication, and needs specialized injection technique to avoid damaging tendons or nerves.

The cellular “bad guys” in your palm

Immune cells like M2 macrophages and mast cells are secretly orchestrating the entire disease process right there in your hand. These cells secrete low levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF), which may not seem significant, but it’s enough to trigger a cascade of problems. The TNF signals through something called the canonical Wnt pathway – basically a cellular communication system – to convert your normal palm fibroblasts into myofibroblasts.

Myofibroblasts are the real troublemakers here. They’re like fibroblasts on steroids, pumping out excessive amounts of collagen that form those rope-like cords in your palm. But here’s where it gets worse: these myofibroblasts create a self-sustaining inflammatory loop by secreting IL-33, which keeps the whole destructive cycle going. It’s like they’re feeding themselves, which explains why the condition progressively worsens over time without intervention.

So you’ve got M2 macrophages and mast cells releasing TNF, which creates myofibroblasts, which then release IL-33 to keep more inflammation going. Each component reinforces the others in a vicious cycle that traditional surgery cannot address.

Here’s the real deal on the drug that could change everything

Adalimumab – you probably know it as Humira, that arthritis drug you’ve seen in commercials – became the star of the RIDD trial when researchers decided to test it on Dupuytren’s nodules. This wasn’t just a shot in the dark; the science behind using an anti-TNF therapy made sense because TNF-alpha plays a key role in the fibrotic process that creates those stubborn cords in your hand.

Finding the sweet spot for the dosage

Phase 2a of the trial tested three different doses: 15 mg, 35 mg, and 40 mg, all injected directly into the nodules. Researchers weren’t messing around – they needed to figure out exactly how much drug would actually make a difference. The winner? The 40 mg dose delivered in 0.4 mL was most effective, outperforming its lower-dose competitors in measurable ways.

What actually happened under the microscope

Lab results showed something pretty exciting when you look at the cellular level. The 40 mg dose significantly reduced levels of alpha-smooth muscle actin and type I procollagen proteins – and if you’re wondering why that matters, these are the exact proteins responsible for creating the thick, rope-like tissue that pulls your fingers down. Fewer of these proteins means less contracture formation.

Your body’s fibroblasts produce these proteins like little factories churning out the building blocks of scar tissue. When Adalimumab blocks TNF-alpha, it tells those factories to slow down production. The reduction in alpha-smooth muscle actin is particularly telling because this protein transforms regular fibroblasts into myofibroblasts – the aggressive cells that contract and create the cord you can feel under your skin.

Does this stuff actually work in real life?

Testing the treatment on real patients

You’re probably wondering if this actually translates beyond the lab bench, right? Researchers undertook a randomised controlled trial involving patients with progressive early-stage disease. Each participant received four injections spaced three months apart, giving the anti-TNF therapy time to work on those stubborn nodules.

The results of this trial were not based solely on patient feedback; they relied on objective data. Scientists employed objective measurements to track exactly what was happening beneath your skin, and the findings were pretty compelling for anyone dealing with this condition.

Softening the nodules and shrinking them down

Researchers used a specialised durometer (a device that measures tissue hardness) to obtain precise readings. Nodule hardness decreased significantly compared to the placebo group – we’re talking measurable differences that you could actually quantify. However, they didn’t stop there; ultrasound imaging provided visual evidence that Attenuation of Dupuytren’s fibrosis via targeting the TNF pathway was effective.

The nodules shrank in size, which doesn’t occur with traditional watch-and-wait approaches. Your hand’s tissue responded to the treatment in two measurable ways: becoming softer and smaller. That’s the kind of dual-action result that could potentially stop the disease before it progresses to the point where you’d need surgery.

Think about what this means for your treatment options. Instead of waiting until your fingers curl so badly that surgery becomes inevitable, you might be able to intervene early. The combination of reduced hardness and smaller nodules suggests that the treatment is reversing some of the fibrotic changes, rather than merely masking symptoms or slowing progression.

So, what’s the catch?

Why do we still need more time?

The trial only tracked patients for 18 months – which sounds decent until you realise Dupuytren’s plays the long game. You’d need at least 10 years of follow-up data to determine whether anti-TNF therapy prevents recurrence of those contractures. That’s the frustrating part about this condition… It’s patient, and it’s persistent.

Right now, doctors are using this treatment off-label because it hasn’t been officially approved for Dupuytren’s. You’re necessarily looking at a promising option that’s still in regulatory limbo, waiting for long-term studies to catch up with the early excitement.

This isn’t for everyone just yet

Anti-TNF therapy only works on early-stage nodules – those soft, tender lumps that haven’t turned into the tough, rope-like cords yet. Once your tissue has matured into established cords made of dense collagen, this treatment won’t help you. Think of it like trying to soften concrete after it’s already set.

Timing is everything here. You need to catch those nodules while they’re still in their inflammatory phase, before the fibrosis takes over and locks everything down. If you’ve already got visible finger contractures or those thick cords running down your palm, you’ve likely missed the window where anti-TNF could make a difference.

How does this compare with the traditional approaches?

Traditional treatments for Dupuytren’s contracture leave you playing a frustrating game of whack-a-mole. Your doctor might offer you collagenase injections or needle fasciotomy, but here’s what they won’t always emphasise upfront: these methods carry 5-year recurrence rates between 65 per cent and 75 per cent. That’s not exactly confidence-inspiring when you’re trying to plan your life around functional hands.

Surgery sounds more definitive, right? Fasciectomy is definitely more invasive, requiring longer recovery times and carrying higher risks. But even going under the knife doesn’t guarantee you’re done with this condition – recurrence rates still range from 12 per cent to 75 per cent. The anti-TNF approach flips this entire paradigm on its head because it’s actually a preventive strategy aimed at the root cause instead of just dealing with symptoms after they’ve already wrecked your hand function.

The problem with the “wait and see” method

Doctors often tell patients to hold off on treatment until the contracture really interferes with daily activities. Sounds reasonable… until you realize you’re basically letting the disease progress unchecked while your fascia continues its slow transformation into rope-like cords. By the time you can’t lay your hand flat on a table anymore, the inflammatory cascade has been doing damage for months or even years.

This reactive approach keeps you one step behind the disease. Your hand loses function gradually, and once those fingers start curling, reversing the damage becomes exponentially harder with each passing month.

Dealing with those pesky recurrence rates

You go through treatment – whether it’s injections, needling, or surgery – and feel that incredible relief when your fingers straighten out again. Then six months later, maybe a year if you’re lucky, you notice that familiar tightness creeping back. With current treatments showing recurrence rates as high as 75 per cent within five years, you’re looking at multiple procedures over your lifetime. Each repeat treatment comes with its own risks, costs, and recovery time.

The financial and emotional toll accumulates rapidly. Each recurrence erodes your optimism and makes you wonder if there’s any point in treating it at all. Some patients end up in this exhausting cycle of temporary fixes, never really getting ahead of the condition because nothing addresses why the disease keeps coming back in the first place.

Anti-TNF therapy alters this equation by targeting the inflammatory signalling that drives fibroblast activity and collagen overproduction. Instead of cutting out or breaking up tissue that’s already contracted, you may be stopping the biochemical process that causes the contracture to form. That’s the difference between bailing water out of a sinking boat and actually plugging the hole.

Summing up

Following this research, you’re looking at what could be a genuine paradigm shift – moving from treating contracted fingers to stopping them before they happen. The RIDD trial participants are still being monitored, and their long-term results will indicate whether this approach holds up over time. But here’s what you need to know right now: if you’ve got high-risk factors like a family history of Dupuytren’s, you developed it at a younger age, or you’re dealing with bilateral involvement, you should be tracking your disease progression carefully. Document everything. Stay updated on how those trial participants are doing years down the line. Because while anti-TNF therapy isn’t sitting on pharmacy shelves as a standard treatment option yet, understanding your specific risk profile puts you in the best position to make informed decisions when – and if – this becomes widely available.

FAQ

Q: What exactly is anti-TNF therapy, and how is it different from current Dupuytren’s treatments?

A: Anti-TNF therapy uses a drug called adalimumab (brand name Humira) that’s already approved for treating rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory conditions. The key difference here is timing and approach: instead of waiting until your fingers are bent and then trying to release them through surgery or injections, this treatment targets the small nodules in your palm before they form the cords that pull your fingers down. Oxford researchers inject the medication directly into those early nodules, and it works by blocking tumour necrosis factor, a protein that triggers the whole disease cascade. What makes this particularly exciting is that it addresses the root cause rather than just dealing with the outcome. Current treatments like needle fasciotomy, collagenase injections, or surgery all wait until you have contractures – fingers that won’t straighten – and then try to break up or remove the diseased tissue. But those approaches don’t stop the disease from coming back, which is why recurrence rates are so high (anywhere from 12% to 75%, depending on which treatment you get). The anti-TNF approach is preventive medicine – stopping the problem before it becomes a problem. In the clinical trial, patients who received the injections observed their nodules soften and shrink, and the effects persisted for at least nine months after the last injection. The drug has a half-life of only 2-3 weeks in the body, so the fact that benefits persisted for that long suggests it might be fundamentally altering the disease process rather than merely temporarily suppressing it.

Q: Am I a good candidate for this treatment, and when might it actually become available?

A: Right now, this treatment isn’t available outside of research trials because adalimumab isn’t approved for Dupuytren’s disease yet – the Oxford study used it “off-label.” The ideal candidates in the trial were people with early-stage disease: you can feel nodules in your palm (usually near the ring or little finger), those nodules are clearly getting bigger or more firm, but you don’t yet have significant contractures where your fingers are permanently bent. If your fingers are already pulled down into your palm, this approach won’t straighten them because it doesn’t dissolve the mature collagen cords that cause contractures. You’d be a particularly strong candidate if you have risk factors for aggressive disease – things like having nodules in both hands, a family history of Dupuytren’s, developing nodules at a younger age (under 50), or having related conditions like Ledderhose disease in your feet or Peyronie’s disease. As for availability… that’s the frustrating part. The 18-month results published to date are promising, but Dupuytren’s disease progresses slowly over the years, and researchers need to follow patients for at least 5-10 years to definitively demonstrate that nodule reduction prevents contractures and preserves hand function long-term. The trial is ongoing with a longer follow-up planned. If those extended results remain favourable, the researchers would need to pursue regulatory approval, which entails additional paperwork, review processes, and potentially additional studies. We’re probably looking at several more years before this becomes a standard treatment option your doctor can prescribe. That said, if you’re interested in participating in research, you could check ClinicalTrials.gov or contact major hand surgery centres to see if they’re enrolling patients in related studies.

Q: What are the risks and side effects of getting anti-TNF injections for Dupuytren’s nodules?

A: The safety profile in the RIDD trial was actually quite good, which is encouraging. The most common issues were minor local reactions at the injection site – things like mild itching, redness, or bruising where the needle went in. But here’s the interesting part: those reactions occurred at similar rates in both the adalimumab group and the placebo group (people who got saline injections), which suggests they’re more related to the injection itself than to the medication. There were no serious adverse events related to the treatment during the 18-month study period. That said, you should understand that adalimumab is a powerful immunosuppressive drug when used systemically (throughout your whole body) for conditions like rheumatoid arthritis. In those cases, it can

Another article that may be of interest. Tarlov Cysts: The Trauma Connection