With your stress levels peaking after a long week, you might be eyeing that kava drink at a bar or a neat little capsule from the health store, thinking it’s a gentle, natural way to unwind. You’re told it’s traditional, plant-based, even kinda wholesome – but you’re not getting the full story. Kava can sedate you, impair your driving, mess with your meds, and in some cases, seriously damage your liver. So before you make it your new nightly ritual, you really need to know what you’re actually signing your body up for. Is Kava Safe?

Key Takeaways:

- Reports of liver injury keep popping up in the literature, and while the exact mechanism isn’t nailed down yet, the pattern is worrying enough that long-term or high-dose kava use should ring alarm bells for hepatotoxicity, plus you see other chronic effects like roughened skin, weight loss, gut issues, sexual dysfunction and just generally poorer health.

- Mixing kava with other stuff is where things can go from sketchy to downright risky – it can boost the sedative punch of alcohol, benzos, barbiturates and other CNS depressants, and may mess with the metabolism of drugs like anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, MAOIs, levodopa and anticoagulants, which makes casual “stacking” with meds a really bad idea.

- For clinicians and regular users alike, the safest mindset is to treat kava like a drug, not a harmless tea: avoid it in young people, pregnancy and breastfeeding, warn about driving and machinery, keep an eye on liver function with ongoing use, and be alert to patterns of heavy, habitual consumption that might not look like classic addiction but can still quietly damage health over time.

What’s the Deal with Kava?

A Quick History

You might picture that first kava experience as a chilled bottle from a health store, but if you were in a village in Fiji or Vanuatu 300 years ago, you’d be sitting in a circle, drinking from a carved wooden bowl at a wedding or chiefs’ meeting. Kava comes from the root of the Piper methysticum plant, and in many Pacific Island cultures, it’s not just a drink; it’s part of the social glue that holds communities together. The root gets ground, soaked, and squeezed into water or coconut milk, then shared in a really deliberate way – one shell at a time, with rules, rituals, and a whole lot of social oversight.

In that setting, you’d probably consume a lot more active compounds than you’d ever get from a couple of capsules. Traditional preparations can deliver anywhere from 750 mg to a massive 8,000 mg of kavalactones in a day, according to New South Wales Health. That level of use evolved in a context where people weren’t driving cars, stacking it with antidepressants, or chasing it with wine after work, which is exactly why copy-pasting “traditional use” into modern Australia is not as simple or safe as the marketing makes it sound.

How It’s Used Today

Fast forward to now, and you’ve got kava turning up in places it never used to be – online stores, health food chains, even the supplement aisle at your local pharmacy. You might see capsules promising “calm in a bottle”, powdered root sold for home brews, or trendy kava bars where people sip coconut shells instead of cocktails after work. Most commercial products contain 50 to 100 mg of kavalactones per capsule, with labels telling you to stay under roughly 250 mg per day, which sounds neat and tidy until you realise there’s no global standard to back it up, just patchy data and marketing optimism.

What makes this messy for you as a consumer is that two products with “kava” on the label can behave very differently in your body. Different plant varieties, extraction methods, and parts of the plant used all change the profile, and hardly any of that nuance makes it onto the box. So you can walk into a kava bar, feel pleasantly chilled after a few shells, then grab a concentrated extract from an online store and have a completely different experience, especially if you’re also on SSRIs, benzos, or you drink alcohol. That mix of easy access, inconsistent dosing, and a reputation for being “natural and safe” is exactly where people start to get into trouble without realising.

In practical terms, you’re likely to meet kava in a few main forms: traditional-style powdered root you mix with water at home, instant drink mixes, standardised extracts, and blended “relaxation” formulas that quietly pair kava with other sedatives like valerian or passionflower. Each one hits slightly differently – powders are often used socially in higher doses, while extracts can deliver a lot of kavalactones in a tiny dose and stick around in your system for up to 9 hours. That matters for really everyday stuff: if you take kava at 8 pm for sleep and then drive to work at 7 am, you can still have measurable sedation, slower reflexes, and impaired coordination, especially if you stacked it with alcohol or a sleeping pill the night before.

Is It Really a “Natural” Relaxant?

You might’ve walked into a chemist, seen a pretty brown bottle labelled “kava – natural stress support” and thought, well, it’s from a plant, how bad can it be? That label quietly skips over the fact that kava’s active chemicals, kavalactones, act as central nervous system depressants, in the same broad family of effect as sleeping tablets, alcohol and some anxiety meds. So while it starts its life as a root in the ground, what ends up in your body is a concentrated psychoactive mix that your liver and brain have to process like any other drug.

On top of that, the “natural” tag completely hides how wildly the dose can swing. Traditional use can range from 750 to 8,000 mg of kavalactones per day, whereas your capsule from the health food aisle might contain only 50 to 100 mg, capped at 250 mg on the label. That gap isn’t just academic – it means you’ve got no built-in safety rails, and you’re largely guessing where the line is between mild relaxation, intoxication and outright toxicity. Even major health services now spell it out: When It Comes to Kava, ‘Natural’ Doesn’t Mean Safe, and the marketing copy on the box definitely won’t.

The How and Why of Its Effects

A lot of people are surprised the first time they drink proper kava, when their tongue goes numb, and their shoulders drop within an hour or two. That weird combo of calm, heavy limbs and slowed thinking is your central nervous system being turned down by kavalactones, which boost inhibitory pathways in your brain and blunt excitatory ones. Peak levels in your blood usually hit somewhere between 1.8 and 3 hours after you take it, then hang around for roughly 9 hours, so you can still feel foggy or unsteady well into the next day.

What makes it tricky is that your experience isn’t just about “how strong” the kava is – it’s about which parts of the plant were used, how it was processed, what you ate, what meds you’re on, and whether alcohol is in the mix. Traditional water-based brews from noble cultivars behave very differently from some modern extracts that may use stems, leaves, or organic solvents. That’s part of why one person can feel pleasantly loose on a small dose, while another, at only slightly higher intake, ends up with muscle weakness, impaired reflexes and full-on intoxication that looks a lot like being drunk or heavily sedated.

What Happens to Your Body When You Drink It

Picture this: you sit in a kava bar, finish a few coconut shells, and by the time you stand up, your legs feel like they’re not quite yours. First, you’ll usually notice the surface stuff – numb lips and tongue, a warm heaviness in your muscles, your shoulders dropping, your racing thoughts slowing down. As kavalactones hit your bloodstream and soak into your brain, coordination and reaction times start to slip, which is why driving after kava is flat-out unsafe, even if you “feel fine”.

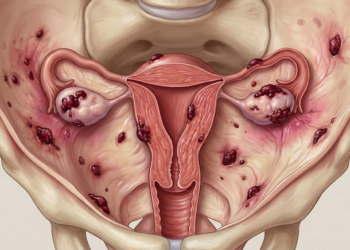

Inside, your liver is quietly doing the hard work, trying to break down a cocktail of compounds that we still don’t fully understand. In some people, especially with regular or high-dose use, this is where things go off the rails: lab reports and case studies link kava to hepatotoxicity, jaundice, liver failure and hospitalisation, sometimes after what users thought were sensible doses. Add alcohol, benzodiazepines, sleeping pills or antipsychotics, and your body has to juggle overlapping depressant effects, higher sedation, slower breathing, nasty interactions with drug metabolism and a sharply higher risk profile, all hiding behind that gentle “natural relaxant” image.

Over the longer term, your body can wear the cost in ways you might not immediately connect to that evening brew: dry, scaly kava dermopathy on your skin, gradual weight loss, chronic gut issues, reduced libido or impotence and an overall slide in health that creeps up slowly. You might not feel “addicted” in the classic sense, but patterns of heavy, ongoing use have been documented in communities, with people drinking daily, stacking shells or cups, and ending up with compounding harms even without chasing a high. If you’re young, pregnant or breastfeeding, the stakes are even higher, because kava crosses into breast milk and psychoactive effects hit harder at lower body weights, so the same “relaxing” dose for someone else can land much more aggressively in your system.

Kava’s Got a Dark Side, Right?

Most people assume that if something has been used in ceremonies for centuries, it must be pretty safe, especially if you can now grab it off a shelf at an Australian pharmacy. But the minute you move kava out of those traditional settings – different plant parts, different extraction methods, concentrated capsules instead of diluted brews – you walk into territory where your body might not react the way you expect. You’ve basically taken a slow cultural practice and turned it into a fast, convenience product, and that shift is where a lot of the real risk creeps in.

In practical terms, you’re dealing with a central nervous system depressant that can make you relaxed, yes, but also drowsy, unsteady, and cognitively dulled for up to nine hours, which is a big deal if you’re driving home from work or juggling other meds. Case reports in Australia and overseas have linked kava to motor vehicle crashes, workplace accidents, and hospital presentations for weird neurological symptoms like temporary paralysis or involuntary movements. It’s not that you’ll automatically end up in an emergency department, but you are playing with a drug that hits the same broad systems as benzos and alcohol – just dressed up with a “natural” label.

The Hepatotoxicity Hype

A lot of people brush off liver warnings as overblown, as if they’re just there so regulators can cover themselves, but the history here is pretty concrete. In the early 2000s, more than 80 cases of suspected kava-related liver injury were reported in Europe and North America, including acute liver failure that led to transplant and death in a small number of patients. That cluster was big enough that several countries temporarily banned or severely restricted kava, not because of one dodgy product, but because clinicians kept seeing the same pattern: previously healthy people developing serious hepatitis while using kava supplements.

What makes it messy for you is that the mechanism still isn’t nailed down. Some data point to certain extraction methods (like ethanolic or acetonic extracts), others to using the wrong plant parts, and others to individual susceptibility or interactions with meds like paracetamol, anticonvulsants, or alcohol. So you can’t assume that because your friend’s been drinking kava nightly for months with “no issues”, you’re in the clear. The uncomfortable truth is that clinicians can’t reliably predict who will tip over into liver injury, or at what dose, which is exactly why regular use without monitoring is a pretty risky experiment on your own liver.

Long-Term Risks You Should Know

It’s easy to think of kava as a “take it when you’re stressed” kind of thing, but in real-world use, people can slide into daily or near-daily drinking or capsule use without even noticing. When that happens, you’re not just chasing relaxation anymore, you’re starting to invite longer-term effects like kava dermopathy – that dry, scaly, yellowish skin change that’s been described in heavy users drinking anywhere from 750 up to 8,000 mg of kavalactones per day. That skin stuff is more than cosmetic, too; it’s often a sign you’ve pushed your body into a pattern of chronic heavy exposure that can also come with weight loss, gut issues, and feeling just generally unwell.

On top of that, there are reports of long-term users developing impotence, poor overall health, and persistent fatigue, especially in communities where kava use is daily and intense. You might not be hitting those traditional levels with a 250 mg supplement, but if you’re stacking products, doubling doses because “it’s natural”, or combining it with alcohol and meds, you’re drifting closer to the kinds of patterns that show up in those case series. So, in the long term, the risk isn’t just one dramatic event; it’s the slow grind on your liver, your skin, your hormones, and the day-to-day functioning that can sneak up on you over months or years.

If you zoom in on those longer-term risks a bit more, the pattern that jumps out is how subtle the early warning signs can be and how easy it is for you to shrug them off. Mild nausea, a bit of abdominal discomfort, odd rashes, feeling “flat” sexually, or just being tired all the time can all be blamed on stress, work, or age, when they might actually be early markers that kava is starting to mess with your liver, your skin, or your endocrine system. The smartest move if you’re using kava regularly is to treat it like any other CNS-active drug: keep doses modest, avoid daily use if you can, get basic bloods done if you’re on it for more than a few weeks, and take new symptoms seriously, especially if they involve jaundice, dark urine, severe fatigue, or persistent skin changes – those are red flags, not “just part of life”.

Drug Interactions – What’s the Risk?

Mixing Kava with Other Meds

You might assume that because kava is sitting on a pharmacy shelf, it quietly minds its own business in your body, but it actually behaves more like a low-key tranquiliser that wants to join in with whatever else you are taking. Kavalactones act as central nervous system depressants, so if you are on meds like benzodiazepines for anxiety, sleeping tablets, antipsychotics, or anticonvulsants, kava can stack the sedation. People describe being far more drowsy, foggy, or unsteady than they expected, and that is exactly what you see when a CNS depressant is quietly doubling down on another one.

There is also the weirder, more unpredictable side of it: kava seems to mess with drug metabolism in ways researchers still have not nailed down. Case reports have flagged reduced effect of levodopa in Parkinson’s patients, possible changes in how anticoagulants behave, and stronger-than-expected responses to antidepressants and antipsychotics when kava is in the mix. So if you are on meds that depend on very steady blood levels – think blood thinners, seizure meds, mood stabilisers – layering kava on top is basically running a chemistry experiment on yourself, with your liver and brain as the test tubes.

Alcohol and Kava – A Recipe for Disaster?

What really catches people out is that kava and alcohol do not just add together; they amplify each other. Both slow your central nervous system, both get processed by your liver, and when you mix them, you tend to get much heavier sedation, clumsier coordination, and much worse judgment than either one alone. Australian and international reports describe people who felt “fine” after a few drinks and some kava, then suddenly hit a wall with extreme drowsiness, trouble walking straight, delayed reflexes, and, in some cases, serious accidents and injuries.

On the liver side, you are basically asking one organ to process two potentially toxic workloads at once, and that is where things get ugly. Historical case clusters of kava-related hepatotoxicity in Europe often involved people who were also using alcohol, and while not every detail is clear, the pattern is: more kava plus regular drinking equals a bigger hit to your liver. So if you are already drinking most days, have fatty liver, hepatitis, or unexplained high liver enzymes, adding kava to your Friday night beers is not “natural wellness” – it is more like slow-motion self-sabotage dressed up as relaxation.

In practical terms, if you are going to use kava at all, treating it like a “soft drink you can mix with anything” is exactly what gets people into trouble. You are looking at more intense intoxication, higher crash risk if you drive, and a higher chance of liver inflammation when alcohol is in the picture, especially if you are using kava most days or pushing higher doses. The safest rule is boring but clear: do not mix kava and alcohol, and if you already have any liver issues or you drink regularly, kava is one supplement you are better off leaving on the shelf.

Are There Safe Alternatives?

So if kava’s looking a bit too risky, what else can you actually use to unwind without smashing your liver or knocking out your reflexes? You’ve basically got two big buckets here: non-drug strategies that change how your brain handles stress, and lower-risk substances or supplements that don’t hit your central nervous system as hard as kava. The interesting part is that some of the things that look a bit boring on the surface – like structured exercise or proper sleep routines – have stronger data behind them than a lot of the fancy “natural” powders on the pharmacy shelf.

There’s also the medication side, which you might already be navigating if you live with anxiety or insomnia. Short-term use of CBT-based apps, sleep restriction therapy, or even a few sessions with a psychologist often gives more benefit than months of chasing the “perfect” herbal relaxant. And if you’re already on something like an SSRI or a low-dose benzodiazepine, adding kava into the mix is a classic example of risk stacking, whereas switching to non-interacting strategies like mindfulness, light therapy, or graded exercise can calm your system without silently increasing sedation, driving impairment, or liver load.

Other Natural Options for Relaxation

When you start comparing kava with other “natural” options, you quickly realise not all plants are playing in the same league. Take chamomile: a 2016 randomised controlled trial in people with generalised anxiety disorder found that long-term use of chamomile extract reduced anxiety scores by about 40%, with mostly mild side effects like digestive upset. Passionflower has some small studies suggesting it helps with anxiety and sleep, but again, the evidence is light-years more modest than the hype on the bottle. And unlike kava, these don’t usually show up in reports of severe liver injury.

On the more practical side, magnesium (especially in glycinate or citrate forms) is often used for sleep and muscle tension, with some data showing improved sleep quality in older adults and in people with low baseline magnesium levels. Lavender oil capsules have a few trials backing them for mild anxiety, and aromatherapy with lavender or bergamot can shift your stress response without sedating you like a CNS depressant. None of these are magic bullets, but they tend to have a much better safety profile than daily kava, especially if you’re already juggling prescription meds, work, and driving.

What Works and What Doesn’t

Once you strip away the marketing, what actually works is usually the stuff that’s been tested in real humans over decent timeframes, not just anecdotes and tradition. Cognitive behavioural therapy, for example, has decades of data and consistently shows effect sizes for anxiety that beat or match many medications in the long term, with zero risk of liver toxicity or drug interactions. Regular aerobic exercise – think 30 minutes of brisk walking or cycling 3 to 5 times a week – has been shown in multiple trials to reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms by 20 to 40%, and it improves sleep architecture rather than just knocking you out.

What tends not to work so well is hopping from one supplement to the next, especially when they all target your central nervous system. Stacking kava, alcohol, sedating antihistamines, and “sleep teas” is how you end up groggy, unsafe to drive, and quietly stressing your liver without really fixing the underlying anxiety. You’re usually better off choosing one or two low-risk tools with actual evidence – say, a chamomile extract with known dosing plus a structured sleep routine – and then building the rest of your plan around lifestyle stuff like light exposure, caffeine timing, and wind-down rituals instead of chasing the next quick-fix capsule.

In practical terms, if you want to separate what genuinely helps you from what’s just good marketing, you can ask a few pointed questions: does this option have randomized controlled trials behind it, or just testimonials; does it interact with CNS depressants, alcohol, or your current meds; and does it target the root (like your stress response, sleep timing, or thought patterns) or just blunt your brain for a few hours. When you run kava through that filter, it starts to look like a relatively high-risk, low-precision tool, while things like CBT, exercise, sleep hygiene, and lower-risk botanicals sit in a very different category – they might be slower and a bit less “dramatic” in the short term, but they’re far safer to keep in your life for months or years without quietly setting you up for the kind of harms you’ve seen reported with heavy or prolonged kava use.

My Take on Kava – Should You Try It?

So where does all this actually leave you – is kava worth a go, or something you should walk right past on the pharmacy shelf? When you strip away the marketing and the “it’s natural so it’s safe” vibe, what you’re really looking at is a central nervous system depressant with unstandardised dosing, documented liver toxicity, and a bunch of unknowns around long-term use. That doesn’t automatically make it evil, but it does mean you shouldn’t treat it like chamomile tea.

In practical terms, kava might have a place for some people as a short-term, low-dose, very intentional experiment, especially if you’re not responding to other strategies and you fully understand the risks. But if you’re thinking of it as a nightly ritual for sleep, combined with a couple of drinks, while also taking meds that affect your brain or your liver, you’re stacking risk on risk. In that scenario, it stops being a “natural relaxant” and starts looking a lot more like a pharmacological gamble you can’t really quantify.

Pros and Cons

When you weigh it up, kava sits in that awkward middle ground: not a banned poison, not a harmless herb, more like something in the same risk neighbourhood as alcohol or benzos-lite. You do get some potential benefits – short-term relaxation, muscle easing, maybe a bump in sleep onset – but you pay for that with impaired reflexes, unpredictable interactions, and the very real possibility of liver damage that can creep up quietly.

Instead of thinking “is kava good or bad”, it’s a lot more useful to ask “good or bad for you, in your exact situation, right now?” If you’re otherwise healthy, on no meds, and using small, infrequent doses, the risk profile is very different to someone drinking high-dose traditional preparations most nights, or layering kava on top of antidepressants and weekend binge drinking. The table below lays it out side-by-side so you can see what you’re actually trading.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| May reduce anxiety and subjective stress in the short term, especially in social situations or evenings | Hepatotoxicity risk: documented cases of liver injury, sometimes severe, particularly with higher or prolonged use |

| Muscle relaxation and sedative effects can help you unwind and fall asleep faster on occasional use | Impaired coordination, slower reflexes, and drowsiness that can affect work, falls risk, and driving safety |

| Chronic heavy use is linked to dermatopathy, weight loss, GI issues, impotence, and generally poor overall health | Potentiates other CNS depressants like benzodiazepines, barbiturates, sleep meds, and alcohol |

| Short half-life (around nine hours) means effects usually wear off by the next day if dosing is modest | Pharmacology is still poorly understood, with big evidence gaps on long-term safety and exact mechanisms |

| Lower-dose capsules (50-100 mg kavalactones) give you more controlled dosing than ad hoc traditional preparations | Huge dosing variability: traditional use can hit 750-8,000 mg kavalactones per day, making risk hard to gauge |

| May feel subjectively “cleaner” than alcohol for some people, with less hangover-type effects at low doses | For some, it offers an alternative to starting prescription anxiolytics, at least for trial periods |

| Can be used intermittently rather than daily, which may limit some harms if you’re disciplined | Harmful use patterns still occur: ongoing high-level consumption in some communities leads to cumulative damage |

| For some, offers an alternative to starting prescription anxiolytics, at least for trial periods | Potential interactions with levodopa, anticonvulsants, MAOIs, antipsychotics, and anticoagulants that your prescriber may not anticipate |

| Traditional cultural use has a long history in Pacific communities when prepared and used in specific ceremonial ways | Modern supplement use often ignores traditional preparation, quality control, and context, which may change risk entirely |

| Easy access in Australia now, with products in pharmacies and health food stores if you decide to trial it | That same easy access can make you underestimate it and slide into regular, unmonitored use without medical oversight |

When to Say No

At some point, you have to draw a line and say “kava just isn’t for me”, and there are a few situations where that line is pretty clear. If you’ve ever had unexplained liver test abnormalities, been told you have fatty liver, hepatitis, or any chronic liver condition, you’re playing with fire, adding a known hepatotoxic agent to the mix, even at low doses. Same story if you drink regularly, especially if you’re sitting in that 10-plus drinks a week territory or doing big weekend sessions – layering kava on top of that is like quietly doubling down on a bet your liver is already losing.

There’s also a hard no if you’re pregnant, trying to conceive, or breastfeeding, because kava crosses into breast milk. No solid data says it’s safe for a developing baby, and “we don’t know, but it’ll probably be fine” isn’t the standard you want to use for your kid. Add in another big red flag: if you’re on anything that affects your brain or blood – antidepressants, antipsychotics, sleep meds, benzos, anticonvulsants, levodopa, anticoagulants – you really shouldn’t be tossing kava into that chemical soup without a very frank chat with your prescriber. And if you know you’re the sort of person who slides from “occasional” to “every night to cope”, kava is unlikely to be kind to you in the long run; your mental health is better served by strategies that don’t quietly ask your liver, your coordination, and your judgement to pay the price.

Summing up

From above, you might be asking yourself, so is kava actually worth the risk for you, or is it more trouble than it’s worth? When you weigh up the sketchy dosing, the liver toxicity signals, the sedation, the driving risks, and all the potential drug interactions, it stops looking like a soft, harmless chill-out drink and starts looking more like a drug that just happens to be sold in a “natural” wrapper. If you’re already on meds, using alcohol, or dealing with any liver issues, your margin for error is pretty thin – and nobody’s really mapped out those boundaries properly yet.

From above, the takeaway is that you can still choose to use kava, but you should treat it with the same respect you’d give a prescription sedative, not like a casual herbal tea you grab off the shelf. That means checking your other medications, avoiding alcohol with it, skipping driving after you’ve had it, and being alert to things like fatigue, abdominal pain, or weird skin changes if you’re using it regularly. If you’re unsure, talk it through with your doctor or pharmacist – and go in with your eyes open, because “natural” doesn’t automatically mean safe, and with kava, that gap between perception and reality is pretty wide.

FAQ

Q: If kava is “natural”, why are people saying it might not be safe?

A: A lot of people first try kava at a friend’s place or in a kava bar and walk away thinking, “Hey, this feels pretty chill, must be safer than pills from the chemist.” That vibe is exactly why it’s exploded across parts of Australia – it’s marketed like a herbal tea that just happens to relax your brain.

The catch is that kava isn’t just some sleepy chamomile. It contains kavalactones, which directly depress your central nervous system, a bit like mild sedatives do. In traditional Pacific Island settings, it’s used in ceremonies, with specific preparation methods and strict cultural rules around how often and how much is consumed. When it gets turned into capsules, powders, or instant drinks in Australia, that whole context vanishes.

On top of that, the evidence base is pretty thin. We’ve got traditional reports, some case series, some small trials – but not robust, long-term, well-controlled research that answers simple questions like “What’s a safe dose if you use it 4 nights a week for 2 years?” So you get people self-medicating anxiety, insomnia, stress, stacking it with other meds, driving after using it, and then being surprised when things go sideways.

So no, “natural” doesn’t mean “safe whenever and however you use it.” Kava sits in that awkward grey zone where it can be helpful for some people, but it is very much a psychoactive drug and needs to be treated that way.

Q: How much kava is too much, and why is dosing such a mess?

A: One of the strangest things about kava is how wildly the dose can change from one setting to another. You might see a neat little bottle in a pharmacy telling you to take 100 mg kavalactones a day, then read that traditional use can reach 8,000 mg per day and think, “Wait, what on earth is going on?”

Data from NSW Health suggests that, in some traditional contexts, people may consume 750-8,000 mg of kavalactones per day. Meanwhile, most commercial products in Australia contain 50-100 mg per capsule, with labels stating, “Do not exceed 250 mg per day.” Those numbers are not even in the same ballpark.

The reason this matters is simple: dosing is not standardised, and the research we have borrows heavily from descriptive accounts of traditional use, which don’t map cleanly onto modern supplement habits. Traditional kava is usually water-based, used intermittently, shared socially, and made from specific parts of the plant. Modern products might use different plant materials, solvents, extraction methods, and be taken daily in a more “medication-like” way.

So when people ask “How much is safe?”, clinicians are stuck piecing together guidance from shaky data, inconsistent products, and very different patterns of use. If you’re using kava regularly and pushing doses beyond label recommendations, you’re imperatively experimenting on yourself and your liver, because nobody has firm long-term safety data for that.

Q: What are the real short-term effects of kava, and can you actually get intoxicated?

A: Anyone who’s had a big session of kava in a community setting will tell you it’s not just “a bit relaxing.” After a few strong bowls, your mouth goes numb, your muscles feel heavy, your reactions slow down, and that “floaty” calm can tip into full-on sedation pretty easily if you’re not careful.

Pharmacologically, kavalactones hit peak levels in your blood about 1.8 to 3 hours after you take them, and they hang around with a half-life of roughly 9 hours. So even if you feel like you’ve mostly “come good” after a few hours, your nervous system may still be very much under the influence. In the short term, people typically report muscle relaxation, drowsiness, and a warm sense of well-being, which is exactly why it’s so tempting for anxiety and sleep problems.

But intoxication is absolutely a thing with kava. At higher doses, people can get wobbly on their feet, have poor coordination, weak muscles, delayed reflexes, and that kind of zoned-out sedation that makes everything feel like it’s moving through syrup. In extreme cases, there have been reports of paralysis in the limbs, involuntary movements, very deep sleep and even deafness. That’s not the chill, harmless herbal tea image you see on product labels.

If you’re taking kava then driving, working at heights, operating machinery, or doing anything where fast reactions matter, you’re taking a real risk. The “it just relaxes me” narrative hides the fact that, at the wrong dose or mixed with the wrong substance, it behaves like a proper sedative drug.

Q: How worried should I be about kava and liver damage, and what about long-term health issues?

A: Stories of people ending up with serious liver problems after using kava have scared a lot of folks away from it completely, while others shrug it off as rare or exaggerated. As usual, the truth sits somewhere in between, which is annoying but also important to sit with for a minute.

We do know that kava has been associated with hepatotoxicity, meaning actual liver injury, in a range of case reports. The exact mechanism is still murky – it’s probably a mix of individual susceptibility, dose, duration, product quality, and sometimes mixing it with alcohol or other meds. But the bottom line is clear enough: liver damage has happened in real people who were using kava, especially at high or prolonged doses.

And it’s not just the liver that can cop it over time. Long-term heavy use has been linked to a distinct skin condition (a kind of dry, scaly dermatopathy), weight loss, gut issues, sexual dysfunction like impotence, and a more general decline in health. You’ll hear clinicians in some regions describe “kava drinkers” who look noticeably unwell – tired, underweight, with that characteristic skin change after years of heavy use.

If you’re using kava regularly, it’s worth treating it like any other drug that can affect the liver. That means watching for symptoms like fatigue, nausea, dark urine, pale stools, itchiness, right upper abdominal pain, or yellowing of the skin or eyes, and getting liver function tests if use is ongoing. Long-term, high-level consumption without medical monitoring is playing with fire, even if the flame doesn’t show up right away.

Q: Can kava interact with my medications or affect driving, and who really shouldn’t be using it?

A: A lot of people grab kava because they want to get off prescription meds, not realising it can still mess with the drugs they’re already on. You might feel like you’re choosing the “safer”, more natural path, but your liver and brain don’t care about the marketing label – they only care about what’s actually in the mix.

Kava has sedating effects that can stack with other central nervous system depressants. So if you’re on benzodiazepines, barbiturates, certain sleep meds, opioids, or you’re drinking alcohol, kava can amplify that drowsiness, slow your reflexes even more, and bump up the risk of serious impairment. The combo of kava and alcohol is particularly rough: deeper intoxication, more drowsiness, worse coordination, and added strain on the liver.

There are also reports and concerns about interactions with levodopa (for Parkinson’s), anticonvulsants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, antipsychotics, and anticoagulants. Kava may interfere with drug metabolism in ways we don’t fully understand yet, which means your usual dose of another medication might suddenly behave differently in your body. That’s especially risky if you’ve got complex mental health or neurological conditions.

Driving is another big one that often gets brushed aside. Data from countries where they’ve actually studied kava in crash-involved drivers show clear impairment in perception, alertness, and response times. If kava makes you feel chilled enough to forget your worries, it’s also chilled your nervous system enough to slow your reactions, and that’s exactly what you don’t want behind the wheel.

As for who should avoid it: kids and adolescents (more intense psychoactive effects with lower body weight), pregnant women, and breastfeeding women should steer clear. Kava passes into breast milk, and we do not have solid safety data in pregnancy or early life. Plus, while kava might not be classically addictive like alcohol or opioids, harmful patterns of high, ongoing use do occur and can gradually wreck health even without classic withdrawal symptoms.