The Hidden Blind Spot in Heart Care: Why Obesity Can Mask Heart Failure Risk—and What We Can Do About It

Key Takeaways

- Obesity raises heart failure risk but lowers circulating natriuretic peptides, leading to underdiagnosis.

- Standard BNP/NT-proBNP thresholds may be too high for people with obesity—consider adjusted cutoffs.

- A multi-signal dashboard (symptoms, exam, imaging, labs) beats reliance on one biomarker.

- Early interventions—weight management, SGLT2 inhibitors, sleep apnea treatment—can alter HF trajectory.

- Clinicians and patients must advocate for context-aware interpretation of heart failure tests.

Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Core Concepts and Mechanisms

- 3. Clinical Evidence and Real-World Impact

- 4. Treatment and Management Approaches

- 5. Prevention and Practical Applications

- 6. Conclusion and Future Outlook

- FAQ

1. Introduction

Let me tell you about two patients who walked into the same clinic on the same day.

Patient A: 58 years old, slender build. She’s been getting winded on the stairs, waking at night short of breath. A natriuretic peptide test comes back high. Alarm bells. Echocardiogram, cardiology referral, treatment plan.

Patient B: 58 years old, similar symptoms, but with obesity. Same test—results “normal.” Reassured, told it’s probably lungs or deconditioning. The problem? She actually has heart failure—just hidden.

This gap in detecting heart failure in people with obesity is a silent crisis. When misread signals mean missed diagnoses, delayed treatment, and worse outcomes, we must ask: how can we read the alarms more clearly?

Obesity and heart failure are colliding epidemics. About 42% of U.S. adults meet criteria for obesity, and more than 6.7 million Americans live with heart failure today—a number projected to keep rising. One in four adults will develop heart failure at some point in life.

You’ll see terms like natriuretic peptides (BNP, NT-proBNP), heart failure guidelines, and obesity heart failure risk. We’ll decode the science, share patient stories, and show how to update our approach—so every heart gets heard.

2. Core Concepts and Mechanisms

Why heart failure is more than “a weak heart”

Heart failure means the heart can’t keep up with the body’s needs—either because it pumps too weakly (HFrEF) or it’s too stiff to fill properly (HFpEF). Many patients shift between categories over time.

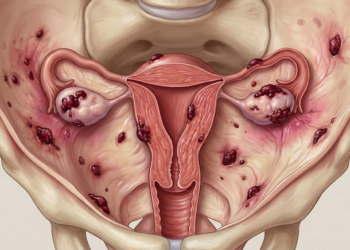

The obesity connection: why body fat strains the heart

- Mechanical load: Extra mass means more blood volume and higher workload, leading to ventricular hypertrophy and stiffness.

- Metabolic stress: Insulin resistance, diabetes, inflammation damage vessels and create myocardial fibrosis.

- Adipose signaling: Fat releases cytokines (leptin, adiponectin) that affect blood pressure, renal function, and inflammation.

- Sleep-disordered breathing: Obstructive sleep apnea spikes nighttime blood pressure and sympathetic drive.

- Comorbidities: Hypertension, kidney disease, fatty liver, arthritis compound risk.

Each 5-unit rise in BMI is linked to a ~41% increase in HF risk.

Natriuretic peptides: the heart’s “help” signals that can be muted by obesity

BNP and NT-proBNP rise when heart muscle stretches, helping the body shed salt, dilate vessels, and counteract blood pressure systems. Clinicians rely on them because they’re usually low in health and climb with cardiac stress. But in obesity:

- Increased clearance: More NPR-C receptors in adipose “net” these hormones.

- Suppressed synthesis: Hyperinsulinemia dampens NP gene expression.

- Enzymatic degradation: Altered neprilysin activity can skew BNP vs. NT-proBNP levels.

It’s like trying to detect smoke with a clogged sensor—fires burn longer before the alarm sounds.

Guidelines and thresholds: the one-size-fits-all problem

U.S. heart failure guidelines use fixed NP cutoffs for diagnosis, but those thresholds may be too high for people with obesity. Many studies show obese individuals with HF have “normal” NP values at the same disease stage as lean patients, leading to false reassurance.

What the “obesity paradox” really means (and doesn’t)

People with obesity and established HF sometimes show better short-term survival than lean counterparts. That’s the “obesity paradox”—likely due to confounders (younger age, nutrient reserves) and not true protection. It doesn’t negate their higher risk of developing HF in the first place.

A staging lens: where we miss risk most

HF stages run from A (at risk) to B (pre-HF), C (symptomatic), D (advanced). NPs often detect Stage B. In obesity, low NPs can hide Stage B, stalling early intervention.

Bottom line on the biology

- Obesity drives HF risk—especially HFpEF—via mechanical, metabolic, inflammatory, and respiratory pathways.

- Natriuretic peptides are consistently lower in obesity despite similar cardiac stress.

- Standard NP cutoffs can miss HF in obesity and overcall it in CKD—advocating for context-aware thresholds.

3. Clinical Evidence and Real-World Impact

In clinics using fixed NP rules, half the population may have obesity. Without adjustment, many at-risk patients remain unflagged—even with structural or symptomatic red flags.

A patient story: Monica’s “normal” test

Monica, BMI 37, ankle swelling and breathlessness. NT-proBNP “normal.” Months later, echo reveals HFpEF. Her NP was falsely low for her body type—a known issue in obesity.

Emergency department snapshot

In acute dyspnea, NPs guide rapid decisions. Proposed obesity-specific cutoffs (reduce by ~⅓ for BMI 30–34.9, by ½ for BMI ≥35) can improve sensitivity—though not yet universally adopted.

How big is the obesity-HF intersection?

- Up to one-third of HF patients meet criteria for obesity.

- ~42% of U.S. adults have obesity.

- One in four adults will develop HF; prevalence rises with obesity.

- Each 5-point BMI gain → ~41% higher HF risk [1].

Guideline drift and the ACC’s 2025 signal

The 2025 ACC Scientific Statement on obesity in HF highlights BMI’s limits and the need for variable NP thresholds by context, including obesity and CKD.

4. Treatment and Management Approaches

Treat the person, not just the peptide. Weight management, HF therapies, sleep apnea treatment, and a multi-signal dashboard form the core.

Weight management: the upstream fix

- Lifestyle: 5–10% weight loss lowers BP, metabolic stress, and cardiac workload.

- Medications: Semaglutide, tirzepatide improve weight and HFpEF symptoms [2].

- Bariatric surgery: Durable weight loss, improved comorbidities, better HF outcomes.

- Team-based care: Dietitians, exercise physiologists, behavioral therapists in cardiometabolic centers.

Heart failure therapies that work across body sizes

- SGLT2 inhibitors (dapagliflozin, empagliflozin)

- ACEi/ARB/ARNI (note: ARNI raises BNP but not NT-proBNP)

- Beta-blockers, MRAs, diuretics

- Exercise and cardiac rehab (low-impact activities)

- CPAP for sleep apnea

- Blood pressure and glucose optimization

Interpreting natriuretic peptides in obesity

- Consider lower NP thresholds (–⅓ for BMI 30–34.9, –½ for BMI ≥35) until standards catch up.

- Use trends over time; a rise from 25 to 110 pg/mL is meaningful.

- Prefer NT-proBNP when on ARNI therapy.

- Interpret higher NPs in CKD cautiously; combine with exam and imaging.

- Never rule out HF solely on a “normal” NP in obesity—pursue further evaluation if suspicion remains.

5. Prevention and Practical Applications

If you’re a patient or caregiver

- Trust your symptoms: orthopnea, PND, ankle swelling, rapid weight gain—speak up.

- Track weight, BP, activity, sleep; share trends with clinicians.

- Ask targeted questions about echocardiography, NP interpretation, and weight-loss supports.

- Make small, sustainable diet and activity changes.

- Manage hypertension, diabetes, cholesterol, kidney health.

- Build a care circle: primary care, cardiology, nutrition, behavioral health.

If you’re a clinician

- Be aware of the NP blind spot in obesity and CKD.

- Use a multimodal assessment: symptoms, exam, echo, lung ultrasound.

- Adopt practical NP adjustments and document rationale.

- Treat obesity as a disease—consider anti-obesity meds and cardiometabolic referrals.

- Start HF-protective therapies early: SGLT2i, BP control, MRAs, sleep apnea therapy.

- Schedule timely follow-up for borderline cases.

- Educate with empathy—focus on health goals, not judgment.

6. Conclusion and Future Outlook

In obesity, heart failure risk is higher but natriuretic peptides read lower. One-size-fits-all thresholds miss risk and delay care. We can close this blind spot by:

- Interpreting NPs in context—especially obesity and CKD.

- Advocating for variable NP thresholds in future guidelines [4].

- Using a multi-signal dashboard: labs, imaging, exam, functional testing.

- Deploying proven therapies: weight management, SGLT2i, ARNIs, CPAP.

- Building multidisciplinary cardiometabolic care as standard.

When the plan fits the person, lives improve. Let’s step beyond rigid thresholds and see every heart clearly.

FAQ

Q: Can a “normal” NT-proBNP rule out heart failure in obesity?

No. In people with obesity, NPs can be falsely low. Clinical suspicion should trigger echo or lung ultrasound even with normal labs.

Q: How much should NP cutoffs be lowered for obesity?

Expert proposals suggest reducing thresholds by ~⅓ for BMI 30–34.9 and ~½ for BMI ≥35, especially in acute settings. Document local protocols.

Q: Which NP should I use on ARNI therapy?

Use NT-proBNP, as sacubitril/valsartan increases BNP levels by neprilysin inhibition.

Q: What weight-loss interventions help heart failure?

Sustainable lifestyle changes, semaglutide/tirzepatide, and bariatric surgery (when appropriate) lower cardiac workload and improve HF symptoms.

Further Reading

- Functional Foods: 7 Science-Backed Benefits for Better Health

- Understanding Chronic Kidney Disease: Causes, Symptoms and Management

- Supporting Patients with Alcohol Use Disorder: From Assessment to Relapse Prevention

- Exploring Holistic Health – A Comprehensive Guide For Everyone

- Recognizing the Signs of Burnout in Healthcare: Strategies for Stress Management and Well-Being

“`